The Early Settlement of Oyster Bay

| |||||||||||||||||||

| the_early_settlement_of_oyster_bay.pdf | |

| File Size: | 5263 kb |

| File Type: | |

A Brief History of Oyster Bay Schools

by John E. Hammond

...The new school house was dedicated on Wednesday, December 27, 1872. Almost 1000 people from the village turned out for the ceremonies. Rev. Charles Wightman pronounced the Invocation and gave a short address...

from The Freeholder, Winter 2000, Volume 4, no. 3. 6-9.

Download complete text below:

| oyster_bay_schools_i.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2366 kb |

| File Type: | |

| oyster_bay_schools_ii.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2202 kb |

| File Type: | |

Adam-Folger-Sampson Cemetery

After twenty-five years the main stone is back where it belongs, resting in its proper place (not a scratch, either). The other big stones are both vertical and in their correct places again. One base repair to go. Now to work on the Derby headstone... Bill Dieffenbach

After twenty-five years the main stone is back where it belongs, resting in its proper place (not a scratch, either). The other big stones are both vertical and in their correct places again. One base repair to go. Now to work on the Derby headstone... Bill Dieffenbach

Artistry in Glass: The Undisputed Master, Our Oyster Bay Neighbor

| |||||||

| tiffany_chronology.pdf | |

| File Size: | 3224 kb |

| File Type: | |

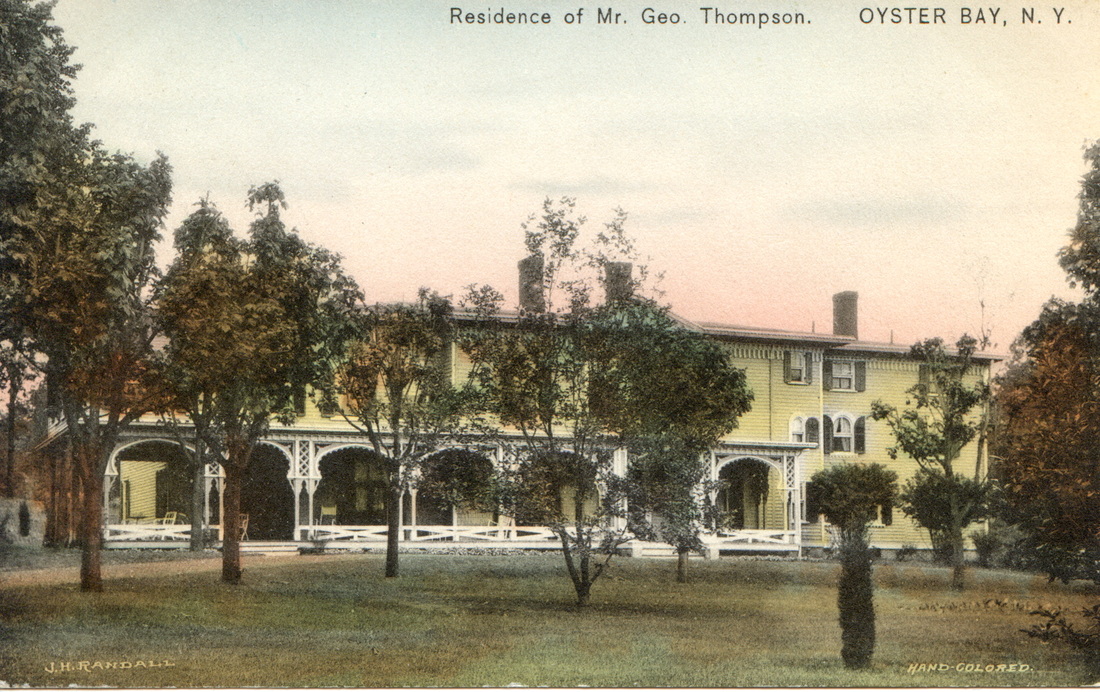

The mystery of typhoid fever was uncovered in Oyster Bay with a woman now known as Typhoid Mary. According to Oyster Bay Historical Society Archivist Nicole Menchise, in the summer of 1906 a wealthy banker rented a home in Oyster Bay from the Thompson family. In August of that year, in a matter of a 10-day period, everyone in the house came down with typhoid fever. Everyone was treated and survived the deadly disease, but when the Thompsons returned to their home, they were concerned about what was brought into it...

Theodore Roosevelt First and Last

by Elizabeth Roosevelt

Coming as he did at the beginning of the twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt was a president involved in a goodly number of firsts. He was the first president to go up in an airplane and the first to go down in a submarine. He was the first to be largely photographed and have movie film made of his endeavors. There are probably other firsts that I have missed.

However, he was the last president to have an equestrian statue. His predecessors in this regard are only a handful. George Washington is to be seen on horseback in Boston, New York, Chicago, and Washington DC, with Andrew Jackson appearing most famously in New Orleans. There is a relief sculpture of a mounted Lincoln in Brooklyn's Grand Army Plaza, where Grant appears as well, though as a Civil War general.

There are in fact three statues depicting Roosevelt on horseback. The one in front of the American Museum of Natural History on New York City's Central Park West portrays Theodore as a hunter accompanied by both African and Native American hunters. It was done by James Earl Frazier. A second statue, by Alexander Phimister Proctor, stands in front of the historical society in Portland, Oregon, a copy of which is now situated at the main entrance to Oyster Bay.

Subsequent presidents have from time to time been photographed on horseback, including Calvin Coolidge, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush, but no sculptors have yet stepped forward to put these chief equestrians up on pedestals.

American equestrian sculpture arose in the nineteenth century and, for the most part, depicted generals at war. And since Roosevelt was the last commander-in-chief to ride into battle, it is probably fitting that he be the last to have an equestrian statue, even if, as all accounts indicate, his service in Cuba involved much more time on foot than in the saddle.

pictured above: Fountain statue at Theodore Roosevelt Sanctuary and Audubon Center in Oyster Bay Cove

However, he was the last president to have an equestrian statue. His predecessors in this regard are only a handful. George Washington is to be seen on horseback in Boston, New York, Chicago, and Washington DC, with Andrew Jackson appearing most famously in New Orleans. There is a relief sculpture of a mounted Lincoln in Brooklyn's Grand Army Plaza, where Grant appears as well, though as a Civil War general.

There are in fact three statues depicting Roosevelt on horseback. The one in front of the American Museum of Natural History on New York City's Central Park West portrays Theodore as a hunter accompanied by both African and Native American hunters. It was done by James Earl Frazier. A second statue, by Alexander Phimister Proctor, stands in front of the historical society in Portland, Oregon, a copy of which is now situated at the main entrance to Oyster Bay.

Subsequent presidents have from time to time been photographed on horseback, including Calvin Coolidge, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush, but no sculptors have yet stepped forward to put these chief equestrians up on pedestals.

American equestrian sculpture arose in the nineteenth century and, for the most part, depicted generals at war. And since Roosevelt was the last commander-in-chief to ride into battle, it is probably fitting that he be the last to have an equestrian statue, even if, as all accounts indicate, his service in Cuba involved much more time on foot than in the saddle.

pictured above: Fountain statue at Theodore Roosevelt Sanctuary and Audubon Center in Oyster Bay Cove

Tennis on Cove Neck

by Elizabeth Roosevelt

The residents of the village have in many cases been tennis players. There was a tennis court at Sagamore Hill and one on the property of W. Emlen Roosevelt across the road from Sagamore in the woods. I believe these were grass courts. I know that the one on the W. Emlen Roosevelt property was destroyed during World War II (to become a corn field). The property of Henry H. Anderson also has a tennis court.

The indoor tennis court (which is a club) was founded by families living on Cove Neck. The founding members were Mrs Henry H. Anderson, George T Bowdoin, Henry E Coe Jr, Oliver B James, George E Roosevelt, Mrs Philip J Roosevelt, Anna L Straus, Mrs Alexander White, and Mr & Mrs Van S Merle-Smith. The Club was incorporated on May 28, 1932, and was built on land owned by the Merle-Smiths.

Club membership expanded during the 1930s to include, as it does today, families outside Cove Neck. During World War II, when many members were in the service and gas was rationed, the club’s operations were suspended. Due to the efforts of Mrs Philip J Roosevelt, Jr, the club was reorganized and resumed operations in 1945. At that point the Roosevelt children and Fritz Coudert were sent to the club to take lessons as a way of getting things started again.

In 1966 the club purchased its property from Mrs Merle-Smith, and membership increased to the present limit of 90 regular members and 65 limited ones.

The indoor tennis court (which is a club) was founded by families living on Cove Neck. The founding members were Mrs Henry H. Anderson, George T Bowdoin, Henry E Coe Jr, Oliver B James, George E Roosevelt, Mrs Philip J Roosevelt, Anna L Straus, Mrs Alexander White, and Mr & Mrs Van S Merle-Smith. The Club was incorporated on May 28, 1932, and was built on land owned by the Merle-Smiths.

Club membership expanded during the 1930s to include, as it does today, families outside Cove Neck. During World War II, when many members were in the service and gas was rationed, the club’s operations were suspended. Due to the efforts of Mrs Philip J Roosevelt, Jr, the club was reorganized and resumed operations in 1945. At that point the Roosevelt children and Fritz Coudert were sent to the club to take lessons as a way of getting things started again.

In 1966 the club purchased its property from Mrs Merle-Smith, and membership increased to the present limit of 90 regular members and 65 limited ones.

TR,Yosemite and John Muir

by Rita Cleary

Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir, Yosemite

In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States, traveled across the country to inspect our National Parks of the American West. Perhaps the most inspiring highlights of that trip were the four days he spent with John Muir, prominent naturalist and founder of the Sierra Club, in the vast wilderness of the Yosemite Valley.

The President arrived in the Yosemite Valley by stagecoach with a massive entourage of dignitaries, journalists and photographers including railroad baron, Edward Harriman, captain of industry, Stephen Mather (borax), the governor of California, the Secretary of the Interior, and naturalist John Muir. President Roosevelt, himself an experienced ornithologist and outdoorsman, had personally invited Muir to come along. In TR’s own words: “I want to drop politics absolutely and just be out in the open with you.”

John Muir eagerly accepted the invitation. In the stagecoach, he sat beside the president as the group rolled down the winding road to the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias and through the famous Wawona Tunnel Tree (now fallen because the tunnel so weakened its base). The entire entourage had its picture taken at the base of the 2,700-year-old Grizzly Giant, the Grove’s largest tree, whose single branch measures 6½ feet in diameter. Roosevelt stood in awe and as the dignitaries departed for a reception and dinner at the Wawona Hotel (today California’s third oldest lodge and still in operation), he and Muir stayed behind. TR had deliberately planned his escape into the wilds with Muir, trusted guide Charlie Leidig and several, sturdy, sure-footed horses.

With only a few blankets against the cold and boundless confidence, they rode into the forest and camped out for three nights. Muir always traveled light, the better to understand the wonders of nature: “If I didn’t have a coat or blanket, I’d warm myself by a small fire and burrow beneath the pine needles at night.” Roosevelt too in his “Hunting in the West” describes a snowy night spent outside, tracking a wounded buffalo. By the glow of a campfire, the two extolled the majesty of the pristine wilderness and discussed how the rocks, trees, plants and animals awe and inspire the human heart, and how this grand creation was fast disappearing, even then as now.

John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt believed firmly that natural beauty restores the human soul. The two men argued the same point. Muir used his time spent with Roosevelt to press for the preservation of the Yosemite whose more than 721,000 acres with elevations from 2100 to over 13,000 feet, were not yet a National Park. He did not mince words: “God has cared these trees and saved them from drought, disease, and a thousand storms. But he cannot save them from sawmills and fools – that is left to the American people.” Roosevelt heartily agreed: “We do not intend our natural resources to be exploited by the few against the interests of the many.”

In their conversations, the two men kept interrupting each other, not with antagonism but with enthusiasm. They chatted long into the night and only pulled their blankets over them very late. One morning before dawn, at the 7,000 foot elevation of Glacier Point, it snowed. They ignored the cold and gazed down at the Half Dome, at El Capitan and the entire expanse of the Yosemite Valley glittering under a crystal-white glaze. Muir was delighted with Roosevelt. Roosevelt described Muir in similar glowing terms.

Most of Yosemite National Park remains today just as Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir saw it. Roads are macadam but still twisted, dangerous and incredibly steep, as when the Sierra range was heaved up and tilted some 10,000 years ago. Parking lots, ranger stations and fire watch stations dot major sights and a hotel and village have been built within the park. The Wawona Lodge still exists on the periphery and many horse and foot trails still lead into the untouched wild. The trails are not for the faint-hearted. They are beset with huge roots, rocks and gushing mountain creeks. A half-day ride into the giant sequoias last summer showed me the trees as Roosevelt and Muir must have seen them. There were times when I felt my horse was climbing stairs or when the downgrade was so steep, I leaned back almost flat on my horse’s rump. We crossed three rivers and climbed up and down grades that I’ve not experienced even in the central Rockies. But Theodore Roosevelt always loved a challenge. He never feared the mysterious or unknown. He met danger head-on - witness his trip into the Amazon when he was well on in years. To him and to John Muir, we owe the establishment of our nation’s parks. Their natural monuments and wild grandeurs are realities which dwarf all the special effects, films, photographs and paintings created by human hands. In 1984, UNESCO recognized Theodore Roosevelt’s and John Muir’s efforts and designated Yosemite National Park a World Heritage Site. As Roosevelt and Muir intended, the Yosemite is sure to inspire us and the peoples of all nations with its grandeur and diversity from generation to generation.

The President arrived in the Yosemite Valley by stagecoach with a massive entourage of dignitaries, journalists and photographers including railroad baron, Edward Harriman, captain of industry, Stephen Mather (borax), the governor of California, the Secretary of the Interior, and naturalist John Muir. President Roosevelt, himself an experienced ornithologist and outdoorsman, had personally invited Muir to come along. In TR’s own words: “I want to drop politics absolutely and just be out in the open with you.”

John Muir eagerly accepted the invitation. In the stagecoach, he sat beside the president as the group rolled down the winding road to the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias and through the famous Wawona Tunnel Tree (now fallen because the tunnel so weakened its base). The entire entourage had its picture taken at the base of the 2,700-year-old Grizzly Giant, the Grove’s largest tree, whose single branch measures 6½ feet in diameter. Roosevelt stood in awe and as the dignitaries departed for a reception and dinner at the Wawona Hotel (today California’s third oldest lodge and still in operation), he and Muir stayed behind. TR had deliberately planned his escape into the wilds with Muir, trusted guide Charlie Leidig and several, sturdy, sure-footed horses.

With only a few blankets against the cold and boundless confidence, they rode into the forest and camped out for three nights. Muir always traveled light, the better to understand the wonders of nature: “If I didn’t have a coat or blanket, I’d warm myself by a small fire and burrow beneath the pine needles at night.” Roosevelt too in his “Hunting in the West” describes a snowy night spent outside, tracking a wounded buffalo. By the glow of a campfire, the two extolled the majesty of the pristine wilderness and discussed how the rocks, trees, plants and animals awe and inspire the human heart, and how this grand creation was fast disappearing, even then as now.

John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt believed firmly that natural beauty restores the human soul. The two men argued the same point. Muir used his time spent with Roosevelt to press for the preservation of the Yosemite whose more than 721,000 acres with elevations from 2100 to over 13,000 feet, were not yet a National Park. He did not mince words: “God has cared these trees and saved them from drought, disease, and a thousand storms. But he cannot save them from sawmills and fools – that is left to the American people.” Roosevelt heartily agreed: “We do not intend our natural resources to be exploited by the few against the interests of the many.”

In their conversations, the two men kept interrupting each other, not with antagonism but with enthusiasm. They chatted long into the night and only pulled their blankets over them very late. One morning before dawn, at the 7,000 foot elevation of Glacier Point, it snowed. They ignored the cold and gazed down at the Half Dome, at El Capitan and the entire expanse of the Yosemite Valley glittering under a crystal-white glaze. Muir was delighted with Roosevelt. Roosevelt described Muir in similar glowing terms.

Most of Yosemite National Park remains today just as Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir saw it. Roads are macadam but still twisted, dangerous and incredibly steep, as when the Sierra range was heaved up and tilted some 10,000 years ago. Parking lots, ranger stations and fire watch stations dot major sights and a hotel and village have been built within the park. The Wawona Lodge still exists on the periphery and many horse and foot trails still lead into the untouched wild. The trails are not for the faint-hearted. They are beset with huge roots, rocks and gushing mountain creeks. A half-day ride into the giant sequoias last summer showed me the trees as Roosevelt and Muir must have seen them. There were times when I felt my horse was climbing stairs or when the downgrade was so steep, I leaned back almost flat on my horse’s rump. We crossed three rivers and climbed up and down grades that I’ve not experienced even in the central Rockies. But Theodore Roosevelt always loved a challenge. He never feared the mysterious or unknown. He met danger head-on - witness his trip into the Amazon when he was well on in years. To him and to John Muir, we owe the establishment of our nation’s parks. Their natural monuments and wild grandeurs are realities which dwarf all the special effects, films, photographs and paintings created by human hands. In 1984, UNESCO recognized Theodore Roosevelt’s and John Muir’s efforts and designated Yosemite National Park a World Heritage Site. As Roosevelt and Muir intended, the Yosemite is sure to inspire us and the peoples of all nations with its grandeur and diversity from generation to generation.

Long Island's Sacred Music, 1830-1860

by Michael Goudket

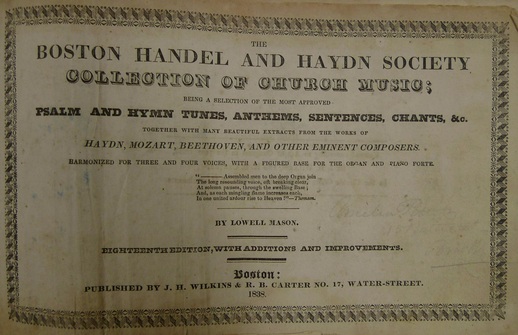

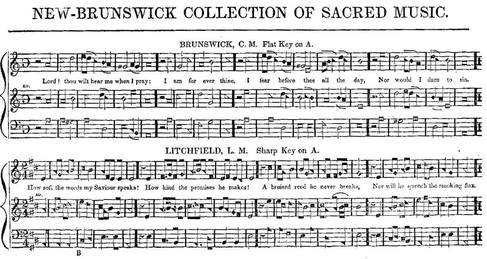

Title page from a good collection of church music describing the kinds of music to be found.

Sacred music was a source of strength for rural Long Islanders facing hard times in the mid-nineteenth century. Life for them was far different from the idyllic vision of farming that we have today. There were years when bad weather killed crops, bank failures wiped out their life savings, diseases struck people and animals without warning. Lurking everywhere was the scourge of alcoholism, the rampant substance abuse problem of the past for which faith was the only known cure. Congregational singing, especially simple hymn and psalm tunes, was (and still is) a way to participate in worship that reinforces faith. Understanding this music is a key to understanding the lives of these early Long Islanders.

The Hymnal

It was the custom for individual members of a congregation to purchase their own hymn books. The family name, or even that of an individual, was often written inside on the fly leaf. Favorite tunes were sometimes marked by the owner and annotations for performance written in. Some books even have additional tunes, which were clipped from another page, pasted in the front or back of the book. So, in addition to knowing which tunes were available, we have an idea of which ones were frequently used.

Advertisements by publishers sometimes offered the books at a quantity discount. This would encourage a congregation to pool their money and all buy the same book to use in worship services. It made finding the tunes easier during the service and the publishers got to sell more books.

Most 19th century volumes of sacred music follow a standard form, and even a standard size. The approximately 6” high by 9” wide volumes usually begin with a section on the rudiments of music. The purchase of a book, often costing the substantial sum of between $3 and $4, meant a commitment to singing. The publishers provided a section on notation, rhythm, and singing advice. Help by more experienced singers and choir masters, regular rehearsals, and a keyboard instrument for support with pitch made it possible for a church choir to be successful. While the congregation would sing the melody of regular musical selections, the choir would sing special things and part harmony.

·

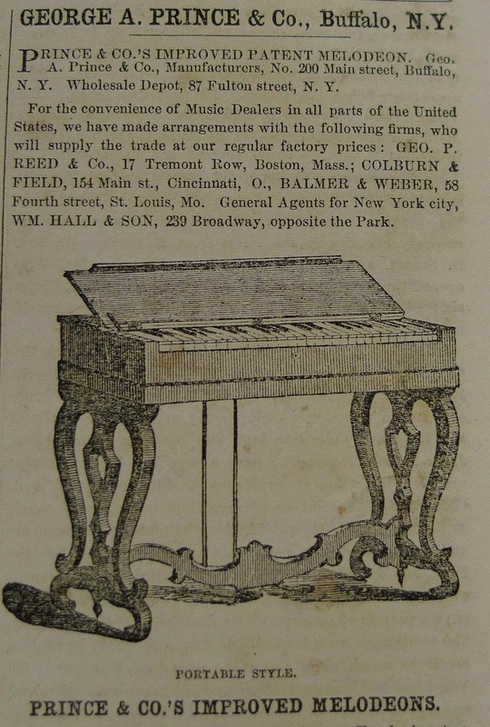

Advertisement for a melodeon, Musical World and New York Musical Times, 4 February 1854

A piano or melodeon in the home of a choir member was acceptable (right). However, having an instrument in the church sanctuary was often prohibited as “ungodly”. This harkens back to the days of the early Massachusetts Pilgrims and anti-Catholic sentiment that prohibited organs as papist travesties. For many years there were no organs in New England protestant churches, but as the singing deteriorated a practical New Englander attitude overcame that prejudice. That singing must have been really awful to get hard nosed puritans to make any change at all.

There were two ways of making printed music staves in 1840’s collections. The first, and most expensive, would be to engrave the music on a single plate. A craftsman would literally carve into a metal plate, usually copper, with an engraving tool. The cavity created was filled with ink and the plate wiped clean of any extra ink. Then the plate was pressed against the paper and the notes appeared. The second way was to use movable type. A staff line, with a clef, time or key signature, a note or rest, was inserted. The lines of music were built up around little blocks of information and a page put together. The pages were inked with a leather pad just like newspaper printing. When enough pages were printed for the proposed edition, the little blocks could be easily rearranged and a different page created from the same basic blocks. Simple music, with a single note or rest, was easily done this way. Chords, as for piano music, had to be made by the more expensive process of engraving or, later on, with somewhat less expensive lithography (see The Freeholder, Fall 2009, Musical Life 1830-1860).

Ingenious New Englanders invented a cello-like instrument just for use in church. This is the Church Bass or Yankee Bass Viol. It is a little bigger than a cello and usually made by a local craftsman. Most are unique and actual shapes and sizes vary considerably. When played, these instruments would double the bass singer’s notes and provide a foundation to the music. The open strings stay true no matter what else is played on the viol and this will keep the singers and instrumentalist from drifting too far away from the original key during performance.

There were two ways of making printed music staves in 1840’s collections. The first, and most expensive, would be to engrave the music on a single plate. A craftsman would literally carve into a metal plate, usually copper, with an engraving tool. The cavity created was filled with ink and the plate wiped clean of any extra ink. Then the plate was pressed against the paper and the notes appeared. The second way was to use movable type. A staff line, with a clef, time or key signature, a note or rest, was inserted. The lines of music were built up around little blocks of information and a page put together. The pages were inked with a leather pad just like newspaper printing. When enough pages were printed for the proposed edition, the little blocks could be easily rearranged and a different page created from the same basic blocks. Simple music, with a single note or rest, was easily done this way. Chords, as for piano music, had to be made by the more expensive process of engraving or, later on, with somewhat less expensive lithography (see The Freeholder, Fall 2009, Musical Life 1830-1860).

Ingenious New Englanders invented a cello-like instrument just for use in church. This is the Church Bass or Yankee Bass Viol. It is a little bigger than a cello and usually made by a local craftsman. Most are unique and actual shapes and sizes vary considerably. When played, these instruments would double the bass singer’s notes and provide a foundation to the music. The open strings stay true no matter what else is played on the viol and this will keep the singers and instrumentalist from drifting too far away from the original key during performance.

·

Note key and time signatures, 5-line staves, and shape notes. L.M. and C.M. denote poetic meter

Shape notation was invented in the early 19th century to help vocalists with little musical skill to read different pitches. The idea was to shape the note heads into triangles, rectangles, and circles to help make pitches more recognizable. In this example (left) from the New Brunswick Collection of Sacred Music by Cornelius Van Deventer, you will see a regular 5 line music staff with standard cleffs, time and key signature. The rests, though a little peculiar to modern musicians, are also standard for the time. The big difference is the shape of the note heads. The pitch of the note determines that shape. Note stems and flags, which determine the duration of the note, remain the same as standard notation (below) While shape notes seemed a good idea, there was little practical advantage to them and so such notation is now no longer used.

·

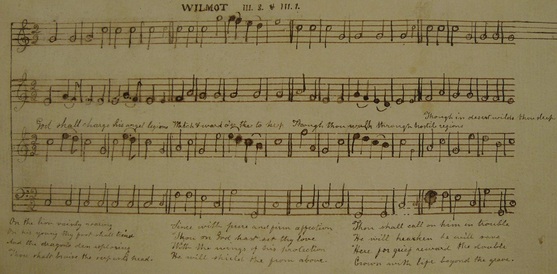

Shape note calligraphy of a song in manuscript laid into a printed song book. Stave lines were ruled with a dip pen

The music

The music for sacred singing in churches by congregations is roughly divided into psalms and hymns. A psalm is based on a biblical psalm text, of which there are 150 in the Book of Psalms. A hymn is based on a non-biblical text composed in relatively recent times but might be as old as the Renaissance. For example, the familiar “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” by Martin Luther (Ein ‘feste Burg) was composed sometime between 1527 and 1529. Other hymns could be composed by the actual author of the printed collection. George F. Root (1820 – 1895), a popular and prolific composer most famous for The Battle Cry of Freedom, is responsible for many fine hymn tunes that appear in period collections.

Very often tunes existed without text. The tune had a name which was followed in the title with initials like LM (long meter) CM (common meter) or SM (short meter) Hymn texts had standard poetic forms that matched these metrical compositions. So, a congregation that knew one tune could use that same tune for different words as needed for the particular occasion.

Though simple, hymn and psalm tunes can have great power. Some of it comes from the text, which may be very poetic and express core values of faith. Some of the power comes from the simplicity of the tune. These are usually an easy to sing because of a narrow pitch range. The tunes progress smoothly from one phrase to another with few unexpected intervals or rhythms. Finding the pitch is easy with intervals of a 3rd, a 5th or an octave. Even the familiarity of singing the same song every Sunday is comforting. All this provides a moving experience for both the singers and the audience.

The Performance

Performing the music in a typical country church was done in several different ways:

A capella unison singing, which is unaccompanied and everyone in the congregation sings the melody.

Responsorial singing is where a leader sings part of the tune first and the congregation, in unison, repeats it. This is sometimes the way new tunes were learned. Once everybody knew the tune, the congregation would simply sing it.

A capella part singing is where an actual choir, which has rehearsed, sings from music. This allows for harmony and is usually three and four part music. When looking over the old hymn and psalm tunes, the actual melody is often in the tenor line and not in the soprano line. This presumed strong male voices, with an occasional alto female voice singing that line as well.

Singing with instrumental support provided a strong foundation to the three ways of singing outlined above. A piano, organ or church bass, though uncommon on Long Island, was a possibility. Other instruments, like the violin or flute, were considered too secular and were generally banned in churches. Though the Bible calls for praising the Lord on harp, there were very few harps and harpers around to do the job in rural areas.

Those familiar with classical music know that there are many amazing compositions for both the Catholic Mass and Protestant service. It is hard to imagine a simple church choir singing Bach chorales or parts of Handel’s Messiah. For this, the simple Long Islanders would go to the bigger churches in the City of Brooklyn. Such music, when written, presumed a professional choir in a large church.

The Concert Hall

People then, as now, appreciate a good concert. Sacred music could be considered entertainment as well as providing a spiritual uplift. Towns organized singing groups for local concerts. Visiting professionals, like the Hutchinson Singers, gave performances in churches and concert halls for which admission was paid. A review of the Hutchinson Singers in the May 3, 1850 BROOKLYN EAGLE reviews a performance given at the Plymouth Church. The Hutchinsons were a singing family that traveled even to Europe while performing American music. The reviewer mentions favorites like “Eight Dollars a Day, The Standing Collar, and Calomel” which were missing from this particular concert. The idea of the concert was thought to be from a Methodist prayer meeting, but the program lacked the variety that the reviewer had come to expect. So, not every concert was a critical success even in 1850.

Strengthening Faith

For us, who can have music at the touch of a switch, it is hard to imagine a world without it. On a 19th century farm, the songs of birds, the sounds of nature, and the voice of someone singing a work song were all the music people would hear during the week. Though the psalms and hymns of church weren't fancy, they were something extraordinary in a life that could be lacking in anything resembling entertainment. The stories told as a part of the service, a rousing sermon, and just being with like-minded people in a group made the worship esperience something moving and special. With this perspective in mind, we will truly understand the lives of those farm families that are our ancestors.

Bibliography

Material for this article was researched from primary sources including manuscripts, mid-19th century printed books of sacred music and from the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper. Readers can search that newspaper online through the Brooklyn Public Library.

http://eagle.brooklynpubliclibrary.org/Default/Skins/BEagle/Client.asp?Skin=BEagle

Readers may also view rare mid-19th century music collections, similar to those mentioned in the text at the Internet Archive website by searching the texts, advanced search, for sacred music (any field).

http://www.archive.org/index.php

Here is a direct link to one such book, published by Oliver Ditson and Company (1856)

http://www.archive.org/stream/celestinaortayl00taylgoog#page/n0/mode/1up

Note: all images courtesy Nassau County Museum Collections

The music for sacred singing in churches by congregations is roughly divided into psalms and hymns. A psalm is based on a biblical psalm text, of which there are 150 in the Book of Psalms. A hymn is based on a non-biblical text composed in relatively recent times but might be as old as the Renaissance. For example, the familiar “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” by Martin Luther (Ein ‘feste Burg) was composed sometime between 1527 and 1529. Other hymns could be composed by the actual author of the printed collection. George F. Root (1820 – 1895), a popular and prolific composer most famous for The Battle Cry of Freedom, is responsible for many fine hymn tunes that appear in period collections.

Very often tunes existed without text. The tune had a name which was followed in the title with initials like LM (long meter) CM (common meter) or SM (short meter) Hymn texts had standard poetic forms that matched these metrical compositions. So, a congregation that knew one tune could use that same tune for different words as needed for the particular occasion.

Though simple, hymn and psalm tunes can have great power. Some of it comes from the text, which may be very poetic and express core values of faith. Some of the power comes from the simplicity of the tune. These are usually an easy to sing because of a narrow pitch range. The tunes progress smoothly from one phrase to another with few unexpected intervals or rhythms. Finding the pitch is easy with intervals of a 3rd, a 5th or an octave. Even the familiarity of singing the same song every Sunday is comforting. All this provides a moving experience for both the singers and the audience.

The Performance

Performing the music in a typical country church was done in several different ways:

A capella unison singing, which is unaccompanied and everyone in the congregation sings the melody.

Responsorial singing is where a leader sings part of the tune first and the congregation, in unison, repeats it. This is sometimes the way new tunes were learned. Once everybody knew the tune, the congregation would simply sing it.

A capella part singing is where an actual choir, which has rehearsed, sings from music. This allows for harmony and is usually three and four part music. When looking over the old hymn and psalm tunes, the actual melody is often in the tenor line and not in the soprano line. This presumed strong male voices, with an occasional alto female voice singing that line as well.

Singing with instrumental support provided a strong foundation to the three ways of singing outlined above. A piano, organ or church bass, though uncommon on Long Island, was a possibility. Other instruments, like the violin or flute, were considered too secular and were generally banned in churches. Though the Bible calls for praising the Lord on harp, there were very few harps and harpers around to do the job in rural areas.

Those familiar with classical music know that there are many amazing compositions for both the Catholic Mass and Protestant service. It is hard to imagine a simple church choir singing Bach chorales or parts of Handel’s Messiah. For this, the simple Long Islanders would go to the bigger churches in the City of Brooklyn. Such music, when written, presumed a professional choir in a large church.

The Concert Hall

People then, as now, appreciate a good concert. Sacred music could be considered entertainment as well as providing a spiritual uplift. Towns organized singing groups for local concerts. Visiting professionals, like the Hutchinson Singers, gave performances in churches and concert halls for which admission was paid. A review of the Hutchinson Singers in the May 3, 1850 BROOKLYN EAGLE reviews a performance given at the Plymouth Church. The Hutchinsons were a singing family that traveled even to Europe while performing American music. The reviewer mentions favorites like “Eight Dollars a Day, The Standing Collar, and Calomel” which were missing from this particular concert. The idea of the concert was thought to be from a Methodist prayer meeting, but the program lacked the variety that the reviewer had come to expect. So, not every concert was a critical success even in 1850.

Strengthening Faith

For us, who can have music at the touch of a switch, it is hard to imagine a world without it. On a 19th century farm, the songs of birds, the sounds of nature, and the voice of someone singing a work song were all the music people would hear during the week. Though the psalms and hymns of church weren't fancy, they were something extraordinary in a life that could be lacking in anything resembling entertainment. The stories told as a part of the service, a rousing sermon, and just being with like-minded people in a group made the worship esperience something moving and special. With this perspective in mind, we will truly understand the lives of those farm families that are our ancestors.

Bibliography

Material for this article was researched from primary sources including manuscripts, mid-19th century printed books of sacred music and from the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper. Readers can search that newspaper online through the Brooklyn Public Library.

http://eagle.brooklynpubliclibrary.org/Default/Skins/BEagle/Client.asp?Skin=BEagle

Readers may also view rare mid-19th century music collections, similar to those mentioned in the text at the Internet Archive website by searching the texts, advanced search, for sacred music (any field).

http://www.archive.org/index.php

Here is a direct link to one such book, published by Oliver Ditson and Company (1856)

http://www.archive.org/stream/celestinaortayl00taylgoog#page/n0/mode/1up

Note: all images courtesy Nassau County Museum Collections

The Long Island Dead Poets' Society

Part XI: The Youngest Poet

by Robert L. Harrison

William Cullen Bryant as a young man

The question arises: who among our poets was the earliest published? Many of our island bards started writing at an early age, while some caught the muse fever much later. But early or late, their literary careers all started, naturally, with a first poem.

William Cullen Bryant received his first acclaim as a poet in 1804 at the age of ten. Among his early verses, which dealt primarily with religious themes, was a poem composed as a school exercise and published in the Northampton Hampshire Gazette in 1807.. Bryant’s father, Dr. Peter Bryant, was said to assist young Bryant in his early poetic endeavors.[i]

Walt Whitman, on the other hand, had his first poem (“Our Future Lot”) published in the Long Island Democrat in 1838 when he was nineteen. He later revised the unsigned poem under the title “Time to Come,” publishing it in the Aurora above the name Walter Whitman[ii].

Another young bard was Alan Dugan (1923-2003), who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1962. Dugan was born in Brooklyn and graduated from Jamaica High School where he wrote occasional verse. After enrolling at Queens College in 1941, he had his first published poems printed in the college literary magazine, winning the Queens College Poetry Prize in 1943. During the Second World War, he was drafted into the Army, where he served as a B-29 engine mechanic in the Pacific.

Another Jamaica High School graduate (1928), Paul Bowles (1910-1999) began his literary career writing for his high school literary magazine, the Oracle. He published his first two poems in the Paris-based magazine transition when he was a mere senior. His first volume of poetry, consisting of two poems, appeared in 1933. During his long lifetime, Bowles became known as a songwriter, composer, short story writer, novelist, bohemian, and true individualist. He and his wife Jane Bowles (Auer), a playwright and novelist, lived briefly in Brooklyn during the 1940s but spent most of their later life in Tangier, Morocco, to which many literary figures made pilgrimages to see them.[iii]

Another teenage poet was John Hall Wheelock (1886-1978), who was said to have written his first poem at the age of nine. Wheelock was a true Long Islander, having been born in Far Rockaway and having spent most of his life in New York City and East Hampton. At Harvard during his freshman year he and Van Wyck Brooks produced a pamphlet of poems titled Verses by Two Undergraduates.[iv] Wheelock would go on to become the senior editor at Charles Scribner and Sons, while writing 13 books of verse. Wheelock was a recipient of many poetry awards, including the Bollinger Prize (1965), and the Gold Medal from the Poetry Society of America for notable achievement in poetry.

A more modern young poet was George Moorse (1936-1999), who grew up in Bellmore. The New York Times bought his first printed poems when he was only fifteen. Fifteen. Moorse graduated from Mepham High School and went on to Hofstra College before transferring to NYU. Moorse became famous as a filmmaker, leaving for Europe in 1959 to produce films from a poet’s perspective. His work is said to have greatly influenced the course of Germany’s postwar film industry. After his death, Moorse was inducted into the Mepham High School Hall of Fame at a ceremony at Hofstra’s University Club.

William Cullen Bryant received his first acclaim as a poet in 1804 at the age of ten. Among his early verses, which dealt primarily with religious themes, was a poem composed as a school exercise and published in the Northampton Hampshire Gazette in 1807.. Bryant’s father, Dr. Peter Bryant, was said to assist young Bryant in his early poetic endeavors.[i]

Walt Whitman, on the other hand, had his first poem (“Our Future Lot”) published in the Long Island Democrat in 1838 when he was nineteen. He later revised the unsigned poem under the title “Time to Come,” publishing it in the Aurora above the name Walter Whitman[ii].

Another young bard was Alan Dugan (1923-2003), who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1962. Dugan was born in Brooklyn and graduated from Jamaica High School where he wrote occasional verse. After enrolling at Queens College in 1941, he had his first published poems printed in the college literary magazine, winning the Queens College Poetry Prize in 1943. During the Second World War, he was drafted into the Army, where he served as a B-29 engine mechanic in the Pacific.

Another Jamaica High School graduate (1928), Paul Bowles (1910-1999) began his literary career writing for his high school literary magazine, the Oracle. He published his first two poems in the Paris-based magazine transition when he was a mere senior. His first volume of poetry, consisting of two poems, appeared in 1933. During his long lifetime, Bowles became known as a songwriter, composer, short story writer, novelist, bohemian, and true individualist. He and his wife Jane Bowles (Auer), a playwright and novelist, lived briefly in Brooklyn during the 1940s but spent most of their later life in Tangier, Morocco, to which many literary figures made pilgrimages to see them.[iii]

Another teenage poet was John Hall Wheelock (1886-1978), who was said to have written his first poem at the age of nine. Wheelock was a true Long Islander, having been born in Far Rockaway and having spent most of his life in New York City and East Hampton. At Harvard during his freshman year he and Van Wyck Brooks produced a pamphlet of poems titled Verses by Two Undergraduates.[iv] Wheelock would go on to become the senior editor at Charles Scribner and Sons, while writing 13 books of verse. Wheelock was a recipient of many poetry awards, including the Bollinger Prize (1965), and the Gold Medal from the Poetry Society of America for notable achievement in poetry.

A more modern young poet was George Moorse (1936-1999), who grew up in Bellmore. The New York Times bought his first printed poems when he was only fifteen. Fifteen. Moorse graduated from Mepham High School and went on to Hofstra College before transferring to NYU. Moorse became famous as a filmmaker, leaving for Europe in 1959 to produce films from a poet’s perspective. His work is said to have greatly influenced the course of Germany’s postwar film industry. After his death, Moorse was inducted into the Mepham High School Hall of Fame at a ceremony at Hofstra’s University Club.

·

Estelle Anna Lewis of Troy, New York

Three Long Island woman also published their poems at a young age. At sixteen, nineteenth-century poet Juliet Isham had her first poem published in the Atlantic Monthly. Brooklyn poet Lucy Hooper, also at sixteen, saw her first poem published in the Long Island Star. Another noted poet, Estelle Anna Lewis of Troy, New York, was twenty when Records of the Heart, her first volume of poems, appeared in 1844.

Nathalia Crane (1913-1998), however, could be the youngest published Long Island bard of them all. Crane, raised in Brooklyn, had her first poem printed in the New York Sun when she was just nine years old. A year later, in 1924, Crane’s first book of poetry, “The Janitor’s Boy And Other Poems,” was published.

With the appearance of her second book, “Lava Road and Other Poems,” in 1925, Edwin Markham, the noted poet and founder of the Brooklyn Poetry Circle, implied that these publications were a hoax, as a girl so young could not produce such work[i]. Several people came to Crane’s defense, among them the noted critic Louis Untermeyer and the poet William Rose Benet. The public followed both sides of the controversy for the next few years in the pages of both the Brooklyn Eagle and New York Times.

Nathalia Crane (1913-1998), however, could be the youngest published Long Island bard of them all. Crane, raised in Brooklyn, had her first poem printed in the New York Sun when she was just nine years old. A year later, in 1924, Crane’s first book of poetry, “The Janitor’s Boy And Other Poems,” was published.

With the appearance of her second book, “Lava Road and Other Poems,” in 1925, Edwin Markham, the noted poet and founder of the Brooklyn Poetry Circle, implied that these publications were a hoax, as a girl so young could not produce such work[i]. Several people came to Crane’s defense, among them the noted critic Louis Untermeyer and the poet William Rose Benet. The public followed both sides of the controversy for the next few years in the pages of both the Brooklyn Eagle and New York Times.

·

Nathalia Crane, Brooklyn poet-prodigy

By the time Crane was fifteen she had three more poetry books in print. In 1927 she won first prize in a national poetry contest based upon Lindbergh’s Trans-Atlantic flight. More than 3,000 entrees were submitted for this contest, but our Brooklyn bard must have put a sting to her doubters when she won [v]. Crane’s winning entry was “The Wings of Lead,” which began

The gods released a vision on a

World forspent and dull:

They sent it as a challenge by the

Sea hawk and the gull.

It roused the Norman eagerness

The albeon cliffs turned red:

You fly the wings of logic-can you

Fly the wings of lead?

Crane would later write two novels and several other books of verse but would never again reach the fame she enjoyed as a poet-prodigy from Brooklyn.

[i] Brown, Charles H. William Cullen Bryant, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. 1971 p20.

[ii] Brasher, Thomas L. editor, The Early Poems and the Fiction, The New York University Press, New York, 1963. P 27.

[iii] Gussow, Mel. Paul Bowles, Dies at 88. The New York Times, 11/19/99 pg B14.

[iv] Quick, Dorothy. Long Island Poet, Long Island Forum, August 1940.

[v] Nathalia Crane, 13, Hits at Critics Who Questioned Her Work, the New York Times, 08/07/26 pg 2

The gods released a vision on a

World forspent and dull:

They sent it as a challenge by the

Sea hawk and the gull.

It roused the Norman eagerness

The albeon cliffs turned red:

You fly the wings of logic-can you

Fly the wings of lead?

Crane would later write two novels and several other books of verse but would never again reach the fame she enjoyed as a poet-prodigy from Brooklyn.

[i] Brown, Charles H. William Cullen Bryant, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. 1971 p20.

[ii] Brasher, Thomas L. editor, The Early Poems and the Fiction, The New York University Press, New York, 1963. P 27.

[iii] Gussow, Mel. Paul Bowles, Dies at 88. The New York Times, 11/19/99 pg B14.

[iv] Quick, Dorothy. Long Island Poet, Long Island Forum, August 1940.

[v] Nathalia Crane, 13, Hits at Critics Who Questioned Her Work, the New York Times, 08/07/26 pg 2

Early Women Photographers of Oyster Bay

by Robert L. Harrison

The woman who makes photography profitable must have, as to personal qualities, good common sense, unlimited patience to carry her through endless failures, equally unlimited tact, good taste, a quick eye, a talent for detail and a genius for hard work. In addition, she needs training, experience, some capital, and a field to exploit.

Frances Benjamin Johnson[1]

The roll call of early photographic pioneers included very few women. Traditional (male) explanations for their exclusion point to the weight and expense of equipment and supplies, as well as prevailing (male) attitudes that women were not as good as men in the new field of photography. Such societal discrimination was reflected in the organization of early photographic competitions, which men and women entered separately, and unequally.

There were a few women, however, who made early breakthroughs in the field. Mary Ann Meade [ii], born in London in 1826, traveled as a young girl with her brothers to France to learn the art of the daguerreotype printing. The Meades later immigrated to America, first to Albany, then to Buffalo, before opening a photography studio in New York City at 233 Broadway. The Meade brothers were quite successful, and on their death it was Mary Ann who closed the doors on their gallery. Known as a camera operator, she had fond memories of meeting Charles Dickens, Edwin Booth, Jenny Lind, and other notables who came to the Meade Brothers studio.

By the 1880s, photography was rapidly growing not merely as an art or a profession but as a hobby, while camera clubs and studios spread out across America. Still, by 1894, the New York World [iii] declared that the only woman photographer in New York City was a Miss Levin, who “turns out work to be the finest of which photographic art is capable.” By 1898,

Mrs. Florida Green was one of three women photographers in the city. By 1900 it is said there were ten, and by 1910, over one hundred working at the trade. Women across the nation were learning the craft and exhibiting their work. Long Island in particular saw four women become important photographic chroniclers of the region’s landscapes and residents.

[1] Johnston, Frances Benjamin. “What a Woman can do with a Camera,” Ladies Home Journal, September, 1897.

[ii] “First Woman Photographer,” Brooklyn NY Daily Eagle. 01/20/1903.

[iii] “Photography Notes,” The New York World. 03/07/1894. Fultonhistory.com

Frances Benjamin Johnson[1]

The roll call of early photographic pioneers included very few women. Traditional (male) explanations for their exclusion point to the weight and expense of equipment and supplies, as well as prevailing (male) attitudes that women were not as good as men in the new field of photography. Such societal discrimination was reflected in the organization of early photographic competitions, which men and women entered separately, and unequally.

There were a few women, however, who made early breakthroughs in the field. Mary Ann Meade [ii], born in London in 1826, traveled as a young girl with her brothers to France to learn the art of the daguerreotype printing. The Meades later immigrated to America, first to Albany, then to Buffalo, before opening a photography studio in New York City at 233 Broadway. The Meade brothers were quite successful, and on their death it was Mary Ann who closed the doors on their gallery. Known as a camera operator, she had fond memories of meeting Charles Dickens, Edwin Booth, Jenny Lind, and other notables who came to the Meade Brothers studio.

By the 1880s, photography was rapidly growing not merely as an art or a profession but as a hobby, while camera clubs and studios spread out across America. Still, by 1894, the New York World [iii] declared that the only woman photographer in New York City was a Miss Levin, who “turns out work to be the finest of which photographic art is capable.” By 1898,

Mrs. Florida Green was one of three women photographers in the city. By 1900 it is said there were ten, and by 1910, over one hundred working at the trade. Women across the nation were learning the craft and exhibiting their work. Long Island in particular saw four women become important photographic chroniclers of the region’s landscapes and residents.

[1] Johnston, Frances Benjamin. “What a Woman can do with a Camera,” Ladies Home Journal, September, 1897.

[ii] “First Woman Photographer,” Brooklyn NY Daily Eagle. 01/20/1903.

[iii] “Photography Notes,” The New York World. 03/07/1894. Fultonhistory.com

Rachel Hicks

Rachel Hicks (1857-1941), a Quaker from Westbury, grew up in the 1695 Hicks-Seaman Homestead, her family’s “Old Place” along the Post Road. During the Civil War the Old Place was reputed to be a stopping ground on the Underground Railroad. As a child, Hicks remembered hearing strange noises late at night, learning (or so she was told) after the war[i] that they came from fugitive slaves.

Hicks, who at a young age exhibited a talent for painting and water colors, discovered photography in the mid-1880s, teaching herself how to use the various cameras and darkroom supplies that existed at the time. Exploiting her prior art training, Hicks composed and documented life on the Old Place and elsewhere in rural Long Island. Besides landscapes and farms, fairs and nearby houses, Hick’s keen eye also recorded the lives of local African-Americans through their daily activities. Nearly one hundred years later the photographs that she took were donated to the Nassau County Photo Archives by Mrs. Frederick J. Seaman. In 1971, these photographs were proudly displayed, first in the Westbury Public Library and later in the Island Trees, Lynbrook, Long Beach, Hicksville, Levittown and Mineola public libraries[ii], using the original 5 x 7 inch glass plates to produce the exhibition’s photographic prints.

Hicks gave up photography after a few active years and by 1900 moved to Roslyn after the Old Place was sold. While living in Roslyn, Hicks became involved in the women’s suffrage movement, and her tremendous energy helped form the Roslyn Nursing Association and the Village Improvement Society. Hicks was the heart of the Hicks-Seaman families until she died in 1941. She left behind the legacy in her photographs, which is now preserved and protected by the Nassau County Photo Archives Center. Although not regarded as a “professional” by her male contemporaries, Rachel Hicks today receives recognition not only for her photography but for her social activism. “Her awareness of both past and present was extraordinary. Dedicated to modern causes, she participated in the women’s struggle to win the vote.[iii]”

[i] Meserole, Richard, “Olde Island Still Lives.” Sunday Daily News, 07/04/71.

[ii] “Best Bets,” New York Magazine, 08/16/1971

[iii] Rachel Hicks, Photographic Compositions of Long Island. Nassau County Department of Recreation & Parks.

Library System handout, 1971.

Hicks, who at a young age exhibited a talent for painting and water colors, discovered photography in the mid-1880s, teaching herself how to use the various cameras and darkroom supplies that existed at the time. Exploiting her prior art training, Hicks composed and documented life on the Old Place and elsewhere in rural Long Island. Besides landscapes and farms, fairs and nearby houses, Hick’s keen eye also recorded the lives of local African-Americans through their daily activities. Nearly one hundred years later the photographs that she took were donated to the Nassau County Photo Archives by Mrs. Frederick J. Seaman. In 1971, these photographs were proudly displayed, first in the Westbury Public Library and later in the Island Trees, Lynbrook, Long Beach, Hicksville, Levittown and Mineola public libraries[ii], using the original 5 x 7 inch glass plates to produce the exhibition’s photographic prints.

Hicks gave up photography after a few active years and by 1900 moved to Roslyn after the Old Place was sold. While living in Roslyn, Hicks became involved in the women’s suffrage movement, and her tremendous energy helped form the Roslyn Nursing Association and the Village Improvement Society. Hicks was the heart of the Hicks-Seaman families until she died in 1941. She left behind the legacy in her photographs, which is now preserved and protected by the Nassau County Photo Archives Center. Although not regarded as a “professional” by her male contemporaries, Rachel Hicks today receives recognition not only for her photography but for her social activism. “Her awareness of both past and present was extraordinary. Dedicated to modern causes, she participated in the women’s struggle to win the vote.[iii]”

[i] Meserole, Richard, “Olde Island Still Lives.” Sunday Daily News, 07/04/71.

[ii] “Best Bets,” New York Magazine, 08/16/1971

[iii] Rachel Hicks, Photographic Compositions of Long Island. Nassau County Department of Recreation & Parks.

Library System handout, 1971.

Frances Benjamin Johnston

Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) was born in Grafton, West Virginia, and raised in a wealthy and well-connected family in Washington D.C. She received her first camera from George Eastman himself and achieved through tenacity, intelligence, and hard work a body of work that was eventually acquired by the Smithsonian Institution.

Johnston at first studied illustration at the Academe Julian in Paris, when she was just twenty years old, before returning to America to join the Art Students League in Washington D.C. There, a New York newspaper commissioned her to provide photographs of President Harrison’s cabinet. Learning to process her own glass negatives[i], she went on to become the first woman to enter the membership of the Washington D.C. Camera Club.

In the following years, Johnston and her camera became a familiar sight in Washington D.C. In 1897, her photograph of Mrs. Grover Cleveland appeared in a full-page spread in the New York Times. When Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, received his Rough Rider uniform, it was Johnston who first asked him to wear it for a photograph. She covered the expositions in Chicago (1893), Paris (1900), Buffalo (1901) and St. Louis (1904). At the Buffalo Exposition, Johnston photographed President McKinley, for the last time, as it turned out, before his assassination[ii].

Three years earlier, in 1898, Johnston had received an assignment to photograph Admiral Dewey and his battleship Olympia that would soon be docking in Naples. Knowing that she would need some credentials to get aboard to meet the Hero of Manila Bay, she rushed to take the Long Island Railroad’s next train to Oyster Bay, where she hired a buggy to take her to Sagamore Hill There, she was told that Mr. Roosevelt was not at home. After she waited over an hour for his return, another servant informed her that he was with his family at the beach. Johnston did indeed find Roosevelt bathing and again waited patiently for a meeting. After listening to Johnson’s story, Roosevelt took her card and wrote

My dear Admiral Dewey

Miss Johnston is a lady whom I personally know and can vouch for. Any promise she may make, she will keep.”

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

With this introduction in hand Johnston caught the ship to Naples the next day. She and the Admiral became fast friends, and Dewey let her have the full run of the ship[iii].

President Roosevelt was not fond of photographers who took pictures of him or his family in private settings. He once caught a photographer trying to photograph him while at church, and after a few unfriendly words from the President the man left. The President instructed his children to run away if anyone with a camera approached them on the White House lawn. Johnston, however, was an exception. She photographed the Roosevelt children many times and formed a friendship with Alice Roosevelt that led her to photograph Alice with her pony, at her debutante ball and for her wedding[iv]. Many of these photographs were published in the leading newspapers and magazines of the time. Johnston was even allowed to advertise portraits of Alice for sale.

Between 1913 and 1917 Johnston formed a partnership with another rising photographer, Mrs. Mattie Edwards Hewitt. The team of Johnston and Hewitt would shoot portraits of wealthy clients and their gardens. While Johnson took most of the photographs, Hewitt was responsible for the printing. While on Long Island, they captured the Marshfield gardens and estates of George Wickersham in Cedarhurst, the Walter Jennings House (Burrwood) in Cold Spring Harbor, and the Ward House (Willowmere) in Roslyn Harbor, traveling as well to Glen Cove to the Pratt estates of Welwyn and Killenworth. Further east, Johnston and Hewitt photographed estates and gardens from the Hamptons to Shelter Island. After the partnership’s dissolution in 1917, Johnston carried on alone with assignments at Laurelton Hall overlooking Cold Spring Harbor, the Doubleday house and gardens (Barberrys) in Mill Neck, the Robert Low Bacon home in Old Westbury, the John Edward Aldred home in Glen Cove, and Coe Hall in Oyster Bay. Later she would travel to California and throughout the South and overseas to execute her commissions[v].

Johnston’s photographic work on Long Island represents only a part of her historic legacy. She was also the first to take successful flash photography in Mammoth Cavern (1894). She was awarded the Palmes Academique by the French Government (1905). And she would be the first woman to have a photographic exhibition in the Library of Congress (1930). During the 1930s she would receive six grants that allowed her to continue her work for the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South. She remained active until just very shortly before her death.

[i] “Photograph of Twenty Millions,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle 10/29/1900 Fultonhistory.com

[ii] Obituary, Niagara Falls Gazette, 06/09/1952. Fultonhistory.com

[iii] Art in Photos, The Daily Piscayune, Louisiana. 12/09/1900. Fultonhistory.com

[iv] “Young America in the White House, the New York Times, 03/17/1907. Sm3.

[v] The Library of Congress has over two thousand of Johnston’s photographs on its web site.

Johnston at first studied illustration at the Academe Julian in Paris, when she was just twenty years old, before returning to America to join the Art Students League in Washington D.C. There, a New York newspaper commissioned her to provide photographs of President Harrison’s cabinet. Learning to process her own glass negatives[i], she went on to become the first woman to enter the membership of the Washington D.C. Camera Club.

In the following years, Johnston and her camera became a familiar sight in Washington D.C. In 1897, her photograph of Mrs. Grover Cleveland appeared in a full-page spread in the New York Times. When Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, received his Rough Rider uniform, it was Johnston who first asked him to wear it for a photograph. She covered the expositions in Chicago (1893), Paris (1900), Buffalo (1901) and St. Louis (1904). At the Buffalo Exposition, Johnston photographed President McKinley, for the last time, as it turned out, before his assassination[ii].

Three years earlier, in 1898, Johnston had received an assignment to photograph Admiral Dewey and his battleship Olympia that would soon be docking in Naples. Knowing that she would need some credentials to get aboard to meet the Hero of Manila Bay, she rushed to take the Long Island Railroad’s next train to Oyster Bay, where she hired a buggy to take her to Sagamore Hill There, she was told that Mr. Roosevelt was not at home. After she waited over an hour for his return, another servant informed her that he was with his family at the beach. Johnston did indeed find Roosevelt bathing and again waited patiently for a meeting. After listening to Johnson’s story, Roosevelt took her card and wrote

My dear Admiral Dewey

Miss Johnston is a lady whom I personally know and can vouch for. Any promise she may make, she will keep.”

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

With this introduction in hand Johnston caught the ship to Naples the next day. She and the Admiral became fast friends, and Dewey let her have the full run of the ship[iii].

President Roosevelt was not fond of photographers who took pictures of him or his family in private settings. He once caught a photographer trying to photograph him while at church, and after a few unfriendly words from the President the man left. The President instructed his children to run away if anyone with a camera approached them on the White House lawn. Johnston, however, was an exception. She photographed the Roosevelt children many times and formed a friendship with Alice Roosevelt that led her to photograph Alice with her pony, at her debutante ball and for her wedding[iv]. Many of these photographs were published in the leading newspapers and magazines of the time. Johnston was even allowed to advertise portraits of Alice for sale.

Between 1913 and 1917 Johnston formed a partnership with another rising photographer, Mrs. Mattie Edwards Hewitt. The team of Johnston and Hewitt would shoot portraits of wealthy clients and their gardens. While Johnson took most of the photographs, Hewitt was responsible for the printing. While on Long Island, they captured the Marshfield gardens and estates of George Wickersham in Cedarhurst, the Walter Jennings House (Burrwood) in Cold Spring Harbor, and the Ward House (Willowmere) in Roslyn Harbor, traveling as well to Glen Cove to the Pratt estates of Welwyn and Killenworth. Further east, Johnston and Hewitt photographed estates and gardens from the Hamptons to Shelter Island. After the partnership’s dissolution in 1917, Johnston carried on alone with assignments at Laurelton Hall overlooking Cold Spring Harbor, the Doubleday house and gardens (Barberrys) in Mill Neck, the Robert Low Bacon home in Old Westbury, the John Edward Aldred home in Glen Cove, and Coe Hall in Oyster Bay. Later she would travel to California and throughout the South and overseas to execute her commissions[v].

Johnston’s photographic work on Long Island represents only a part of her historic legacy. She was also the first to take successful flash photography in Mammoth Cavern (1894). She was awarded the Palmes Academique by the French Government (1905). And she would be the first woman to have a photographic exhibition in the Library of Congress (1930). During the 1930s she would receive six grants that allowed her to continue her work for the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South. She remained active until just very shortly before her death.

[i] “Photograph of Twenty Millions,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle 10/29/1900 Fultonhistory.com

[ii] Obituary, Niagara Falls Gazette, 06/09/1952. Fultonhistory.com

[iii] Art in Photos, The Daily Piscayune, Louisiana. 12/09/1900. Fultonhistory.com

[iv] “Young America in the White House, the New York Times, 03/17/1907. Sm3.

[v] The Library of Congress has over two thousand of Johnston’s photographs on its web site.

Mattie Edwards Hewitt

Mattie Edwards Hewitt (1869-1956) was born in St Louis to a middle-class family and studied art before marrying Arthur Hewitt. Her husband earned a living as a photographer and taught her to be his darkroom assistant. During the Pan American Exposition in 1901, Hewitt met Frances Benjamin Johnston who recognized her appreciable printing talents. Soon, Johnston began to mail her negatives to Hewitt for developing and printing[i]. After Hewitt divorced her husband in 1909, she moved to New York City and opened a studio with Johnston (1913)[ii], specializing in portrait, architecture and garden photography. After their professional and personal separation, Hewitt took up landscape photography and achieved some success over two decades in photographing the gardens and homes of the wealthy. Hewitt, like Johnston wielded a weighty field camera, hiring an assistant to carry it from estate to estate, while arranging her commissions to minimize the time and effort she expended in travel. The leading home-and-garden periodicals regularly published her work, providing her with additional income.

In the Town of Oyster Bay alone, Hewitt photographed the following gardens and estates[iii]

1918: Mrs. Herbert Harriman, Jericho.

1919: Egerton L. Winthrop, Muttontown.

1920: G. Bertram Wood, Oak Knoll, Oyster Bay. Mrs. Benson Flagg, Apple House, Brookville.

1921: Dr. Robert Fowler, Oyster Bay. William R. Coe, Planting Fields, Oyster Bay.

1922: Henry Sanderson, La Selva, Oyster Bay.

1923: Myron C. Taylor, Locust Valley.

1924: Mrs. Louis M. Greer, Bayville. Mrs. Nils Johaneson, Locust Valley. Isaac Cozzens, Mapleknoll, Locust Valley.

1925: Charles E.F. McCann, Oyster Bay.

1926: Artemas Holmes, Brookville. Ira Richards, Jr., Locust Valley. Robert C. Winmill, Mill Neck.

1927: Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Sagamore Hill, Cove Neck. Mrs Charles L. Tiffany, Laurel Hollow.

1928: Mrs. Robert Leftwick Dodge, Sefton Manor, Mill Neck. Mrs. F.A. Mitchell, Brookville.

1929: Mrs. C. O’Donnell, Oyster Bay. Mrs. Edward R. Stettinius, Locust Valley. Dr. John A. Vietor, Cherrywood, Locust Valley. Mrs. Harrison Williams, Oak Point, Bayville. Mrs. Walter Farwell, Mallow, Syosset.

1930: Mrs. C. Porter Wilson, Mill Neck. Franklin B. Lord, Syosset. Mrs. Walter Maynard, Jericho.

1931: Grover Loening, Mill Neck. Mrs. Chalmers Wood, Syosset. Mrs. Wyllys Rossiter Betts, The Pebbles, Syosset. Mrs. James A. Burden, Woodside, Syosset. Mrs. Paul Hammond, Muttontown Lodge, Syosset. Dr. J.P. Hoguet, Oak Lawn, Locust Valley.

1932: John P. Kane, Locust Valley. Irving Cox, Mill Neck.

1933: Mrs. Joseph Kerrigan, Oyster Bay.

1934: Mrs. George Bullock, Centre Island. Mrs. Henry P. Davison, Apple Dore, Locust Valley.

1936: Mrs. Edgar Leonard, Oyster Bay.

1937: Mrs. George de Forest Lord, Syosset.

1941: Scott Rufus, Locust Valley.

Hewitt pursued her career into the early 1950s before her death in Boston in 1956. Over 25 years later, the first exhibition of her work appeared at Wave Hill’s Glyndor Gallery in the Bronx. As recently as 2011 an exhibition presented by The Photo Archive of Nassau County opened during the Long Island Fair at Old Bethpage Restoration Village.

The entire Mattie Edwards Hewitt photography collection might once have been lost but for a fortunate chain of events that saved it[iv]. When Hewitt moved to Boston, her entire life’s work of over 12,000 photos and negatives remained left behind at the New York studio of Richard Averill Smith (1897-1971), and early Hewitt protégé. When Smith died in Levittown in 1971, his entire commercial photography collection, along with Hewitt’s work, remained in boxes at his home. Smith’s associates, in cleaning out his house, called nearby historic societies and libraries to take possession. None did until Richard Winsche, Historian of the Nassau County Museum System, discovered that the Town of Hempstead had scheduled a trash pickup for the collection. Winsche rushed over to the house and, impressed with the historical value of the collection, agreed at once to its donation to Nassau County[v].

[i] Close, Leslie Rose, Portrait of an Era in Landscape Architecture, the Photographs of Mattie Edwards Hewitt. Wave Hill catalog, September, 1983.

[ii] Arthur Hewitt was an active photographer with many magazine/newspaper credits to his name. Most articles state that they divorced in 1909, yet I have seen Mattie list herself as a widow.

[iii] Gary Hammond of the Nassau County Museum Division complied a listing of the Mattie Edwards Hewitt Collection in February, 1988.

[iv] Per phone interview with Mr. Richard Winsche, 07/04/2012.

[v] The Mattie Edwards Hewitt Photo Collection of over 5,000 prints and negatives are preserved by the Photo Archives Center, County of Nassau, Department of Parks Recreation & Museums. (516) 572-8410.

In the Town of Oyster Bay alone, Hewitt photographed the following gardens and estates[iii]

1918: Mrs. Herbert Harriman, Jericho.

1919: Egerton L. Winthrop, Muttontown.

1920: G. Bertram Wood, Oak Knoll, Oyster Bay. Mrs. Benson Flagg, Apple House, Brookville.

1921: Dr. Robert Fowler, Oyster Bay. William R. Coe, Planting Fields, Oyster Bay.

1922: Henry Sanderson, La Selva, Oyster Bay.

1923: Myron C. Taylor, Locust Valley.

1924: Mrs. Louis M. Greer, Bayville. Mrs. Nils Johaneson, Locust Valley. Isaac Cozzens, Mapleknoll, Locust Valley.

1925: Charles E.F. McCann, Oyster Bay.

1926: Artemas Holmes, Brookville. Ira Richards, Jr., Locust Valley. Robert C. Winmill, Mill Neck.

1927: Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Sagamore Hill, Cove Neck. Mrs Charles L. Tiffany, Laurel Hollow.

1928: Mrs. Robert Leftwick Dodge, Sefton Manor, Mill Neck. Mrs. F.A. Mitchell, Brookville.

1929: Mrs. C. O’Donnell, Oyster Bay. Mrs. Edward R. Stettinius, Locust Valley. Dr. John A. Vietor, Cherrywood, Locust Valley. Mrs. Harrison Williams, Oak Point, Bayville. Mrs. Walter Farwell, Mallow, Syosset.

1930: Mrs. C. Porter Wilson, Mill Neck. Franklin B. Lord, Syosset. Mrs. Walter Maynard, Jericho.

1931: Grover Loening, Mill Neck. Mrs. Chalmers Wood, Syosset. Mrs. Wyllys Rossiter Betts, The Pebbles, Syosset. Mrs. James A. Burden, Woodside, Syosset. Mrs. Paul Hammond, Muttontown Lodge, Syosset. Dr. J.P. Hoguet, Oak Lawn, Locust Valley.

1932: John P. Kane, Locust Valley. Irving Cox, Mill Neck.

1933: Mrs. Joseph Kerrigan, Oyster Bay.

1934: Mrs. George Bullock, Centre Island. Mrs. Henry P. Davison, Apple Dore, Locust Valley.

1936: Mrs. Edgar Leonard, Oyster Bay.

1937: Mrs. George de Forest Lord, Syosset.

1941: Scott Rufus, Locust Valley.

Hewitt pursued her career into the early 1950s before her death in Boston in 1956. Over 25 years later, the first exhibition of her work appeared at Wave Hill’s Glyndor Gallery in the Bronx. As recently as 2011 an exhibition presented by The Photo Archive of Nassau County opened during the Long Island Fair at Old Bethpage Restoration Village.

The entire Mattie Edwards Hewitt photography collection might once have been lost but for a fortunate chain of events that saved it[iv]. When Hewitt moved to Boston, her entire life’s work of over 12,000 photos and negatives remained left behind at the New York studio of Richard Averill Smith (1897-1971), and early Hewitt protégé. When Smith died in Levittown in 1971, his entire commercial photography collection, along with Hewitt’s work, remained in boxes at his home. Smith’s associates, in cleaning out his house, called nearby historic societies and libraries to take possession. None did until Richard Winsche, Historian of the Nassau County Museum System, discovered that the Town of Hempstead had scheduled a trash pickup for the collection. Winsche rushed over to the house and, impressed with the historical value of the collection, agreed at once to its donation to Nassau County[v].

[i] Close, Leslie Rose, Portrait of an Era in Landscape Architecture, the Photographs of Mattie Edwards Hewitt. Wave Hill catalog, September, 1983.

[ii] Arthur Hewitt was an active photographer with many magazine/newspaper credits to his name. Most articles state that they divorced in 1909, yet I have seen Mattie list herself as a widow.

[iii] Gary Hammond of the Nassau County Museum Division complied a listing of the Mattie Edwards Hewitt Collection in February, 1988.

[iv] Per phone interview with Mr. Richard Winsche, 07/04/2012.

[v] The Mattie Edwards Hewitt Photo Collection of over 5,000 prints and negatives are preserved by the Photo Archives Center, County of Nassau, Department of Parks Recreation & Museums. (516) 572-8410.

Jessie Tarbox Beals

Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870-1942) became America’s first female news photographer. Born in Hamilton, Ontario, on December 23, 1870, she later became a school teacher in several small towns in Massachusetts. At 18 years of age, Beals won a camera for selling magazine subscriptions and in a few weeks made enough money from her photography to buy a better camera. In 1893 she covered the Chicago Exposition, where she may have met Frances Johnston.

In 1897 Beals married Alfred Tennyson Beals, whom she trained as her darkroom assistant. During this time Beals’ published photographs often appeared unaccredited in the eastern newspapers. In 1902, she was hired by the Buffalo Courier as a staff photographer. Two years later, she was assigned the St. Louis Exposition, becoming the official photographer of the fair for the New York Herald Tribune and a number of other newspapers. Known to shoot from high ladders and even balloons, she received the Fair Committee’s Gold Medal for her work.

Beals followed President Theodore Roosevelt throughout his appearances at St Louis, hiring an assistant to bring her extra photographic plates as needed while covering the President. After some 32 photos were taken, President Roosevelt turned to his companion with a broad smile and exclaimed: “Where in thunder does that woman get her plates? Is she a perambulating factory?”[i]

It was Colliers Weekly that hired Beals to cover President Roosevelt’s 1905 inauguration, the only woman with a press permit for the event. Later that year, when she heard that there would be a reunion of the Rough Riders in San Antonio, Beals went to the White House seeking permission to cover the event. Roosevelt refused her, saying it was a stag affair. Beals stood her ground but came away empty handed. Roosevelt must have changed his mind, for she soon received his card with the following inscription: “The bearer, Mrs. Jessie Tarbox Beals, is a member of the presidential party and as such is commended to the courtesy of those when this card is presented.” When Roosevelt arrived in San Antonio, he spotted Beals right away, saying, “There she is!” to his staff. Beals happily photographed the reunion, lugging her camera around, shooting from trees, and almost being “trampled by snorting bucking broncos[ii].”

Beals developed a long and successful career in portrait, news, and landscape photography, while her Greenwich Village street scenes in particular revealed her ever-present social awareness. She did, however, later express regret that she did not take care to focus her efforts more effectively.

[i] New York Herald, magazine section, 02/02/1908. P11

[ii] Colley, Marion T. “How A Poet-Photographer Found Her Niche In Life,” The Evening Post, 07/30/1920. Futonhistory.com.