The de Kay Family

Grave of George Coleman de Kay

by Robert L. Harrison

In the middle of the summer of 1850, a Federal census taker knocked on the door at The Locusts, a fine house off East Main Street in Oyster Bay. Doctor James de Kay, the owner, was not at home but his sister-in-law and her seven children were. Thus they entered the historical record of Oyster Bay—a remarkable family that, as adventurers, poets, editors, soldiers, scientists, translators, and writers—became in so many ways a part of the American fabric.

On a rainy Friday this past June [2011], a single bagpiper played at the grave of Commodore George Coleman de Kay. A procession of Hibernians, led by Nassau County Legislator Dennis Dunne, Sr. who laid a wreath on the Commodore’s grave, all expressed their thanks to the memory of a true American hero of the Irish famine.[i] All were silent outside St. George’s Episcopal Church in Hempstead as the Rev. P. Allister Rawlins said a few words in prayer as the rain seemed to let up. It was over 160 years ago in 1849 that the Commodore’s relatives came down from Oyster Bay and beyond to attend his funeral here. There were dignitaries and friends also who gathered at St. George’s that day, for the Commodore was a well-known American hero at the time.[ii]

George Coleman de Kay (1802-1849), was born in New York City, the son of George de Kay, a sea captain, and Catherine Coleman. Both of his parents died early, and young George, who was to have attended college, instead pursued a life of seamanship under the master shipbuilder Henry Eckford (1775-1832). It was in 1826, at the age of 24, that he sailed one of Eckford’s ships down to Buenos Aires, and found that the harbor was blocked due to a war between the Argentine Republic and Brazil over the territory of Banda Oriental, which later became Uruguay. It was then that de Kay volunteered to join the Argentine Navy in this conflict. He was given command of an eight-gun brig and soon proved to be one of the most daring sea captains in this conflict by capturing four ships in battle. He was then given command of a larger ship, the Brandzen, which later in a furious engagement defeated the Cacique, a vessel twice its size. Because of his brilliant seamanship, de Kay was soon promoted to lieutenant colonel and later Commodore. As Commodore de Kay, he took both ships on a victory cruise in the Caribbean, then further north to New York where he was cheered as “the Young Commodore of the Spanish Main.” Returning to Buenos Aires in June 1828, de Kay faced a squadron of Brazilian warships which pursued his Brandzen until he scuttled it, saving his crew from surrender.

In the middle of the summer of 1850, a Federal census taker knocked on the door at The Locusts, a fine house off East Main Street in Oyster Bay. Doctor James de Kay, the owner, was not at home but his sister-in-law and her seven children were. Thus they entered the historical record of Oyster Bay—a remarkable family that, as adventurers, poets, editors, soldiers, scientists, translators, and writers—became in so many ways a part of the American fabric.

On a rainy Friday this past June [2011], a single bagpiper played at the grave of Commodore George Coleman de Kay. A procession of Hibernians, led by Nassau County Legislator Dennis Dunne, Sr. who laid a wreath on the Commodore’s grave, all expressed their thanks to the memory of a true American hero of the Irish famine.[i] All were silent outside St. George’s Episcopal Church in Hempstead as the Rev. P. Allister Rawlins said a few words in prayer as the rain seemed to let up. It was over 160 years ago in 1849 that the Commodore’s relatives came down from Oyster Bay and beyond to attend his funeral here. There were dignitaries and friends also who gathered at St. George’s that day, for the Commodore was a well-known American hero at the time.[ii]

George Coleman de Kay (1802-1849), was born in New York City, the son of George de Kay, a sea captain, and Catherine Coleman. Both of his parents died early, and young George, who was to have attended college, instead pursued a life of seamanship under the master shipbuilder Henry Eckford (1775-1832). It was in 1826, at the age of 24, that he sailed one of Eckford’s ships down to Buenos Aires, and found that the harbor was blocked due to a war between the Argentine Republic and Brazil over the territory of Banda Oriental, which later became Uruguay. It was then that de Kay volunteered to join the Argentine Navy in this conflict. He was given command of an eight-gun brig and soon proved to be one of the most daring sea captains in this conflict by capturing four ships in battle. He was then given command of a larger ship, the Brandzen, which later in a furious engagement defeated the Cacique, a vessel twice its size. Because of his brilliant seamanship, de Kay was soon promoted to lieutenant colonel and later Commodore. As Commodore de Kay, he took both ships on a victory cruise in the Caribbean, then further north to New York where he was cheered as “the Young Commodore of the Spanish Main.” Returning to Buenos Aires in June 1828, de Kay faced a squadron of Brazilian warships which pursued his Brandzen until he scuttled it, saving his crew from surrender.

II.

Henry Eckford

Leaving the conflict behind him, the young Commodore (now 27) came back to New York City and enjoyed mingling with members of high society.[iii] In 1831, another adventure awaited the Commodore, as his friend, Henry Eckford allowed him to captain his newly built ship, the United States on a voyage to Turkey, where Eckford, the Commodore, and his brother James Ellsworth de Kay, a physician, were greeted by Sultan Mahmond II. The Sultan at first thought the ship was a gift (after which, realizing his error, he purchased it). Mahmond II was so impressed with Eckford’s shipbuilding abilities that he soon hired him to construct a fleet for the Ottoman Navy. In November 1832 Eckford apparently died of Asiatic cholera in Constantinople and was brought back to America in a ship bearing his name. The flags of New York City were lowered to half-staff when his body arrived, an honor given only to those of great importance.[iv]

Henry Eckford was laid to rest at St. George’s Cemetery in Hempstead, his monument standing near the Commodore’s. The Commodore’s mentor and friend, he was also an American hero in his own right. Born in Scotland, he immigrated to Canada to learn shipbuilding from his uncle. After mastering his trade, Eckford came to New York City to expand his business and in 1799 married Marion Bedell of Hempstead at St. George’s Church. When the War of 1812 was declared, Eckford joined other shipbuilders at Sacket’s Harbor and Oswego, New York. Soon he was the head designer and builder of many of our navy ships, small and large. It was through his activity and that of a few other shipbuilders, that the United States Navy held control of the Great Lakes during the war.

In 1816, Eckford’s daughter Sarah married Joseph R. Drake, who was to become one of the most celebrated American poets of the early 19th century. Before Drake died as a young man in 1820, his poems were collected and transcribed by James Ellsworth de Kay. On his deathbed, Drake protested this attention to his life’s work and said to de Kay, “Burn them—they are valueless.”[v] Fortunately, most of the poems survived and were published later in the 1830s. When Drake died, he left behind his wife Sarah and his only daughter, Janet Drake, named for her aunt (who herself married James Ellsworth de Kay in 1821).

Eckford’s fame as a shipbuilder being well known, he accepted a position as chief naval constructor at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Besides shipbuilding, Eckford served in the New York State Legislature, ran for Congress, and was involved in a scandal with Tammany Hall. Eckford was never convicted of any crime, but he did demand a public apology from the New York District Attorney Hugh Maxwell. When the apology never came, Eckford challenged Maxwell to a duel but was ignored. Eckford soon went back to private shipbuilding, building the aforementioned United States.[vi]

Henry Eckford was laid to rest at St. George’s Cemetery in Hempstead, his monument standing near the Commodore’s. The Commodore’s mentor and friend, he was also an American hero in his own right. Born in Scotland, he immigrated to Canada to learn shipbuilding from his uncle. After mastering his trade, Eckford came to New York City to expand his business and in 1799 married Marion Bedell of Hempstead at St. George’s Church. When the War of 1812 was declared, Eckford joined other shipbuilders at Sacket’s Harbor and Oswego, New York. Soon he was the head designer and builder of many of our navy ships, small and large. It was through his activity and that of a few other shipbuilders, that the United States Navy held control of the Great Lakes during the war.

In 1816, Eckford’s daughter Sarah married Joseph R. Drake, who was to become one of the most celebrated American poets of the early 19th century. Before Drake died as a young man in 1820, his poems were collected and transcribed by James Ellsworth de Kay. On his deathbed, Drake protested this attention to his life’s work and said to de Kay, “Burn them—they are valueless.”[v] Fortunately, most of the poems survived and were published later in the 1830s. When Drake died, he left behind his wife Sarah and his only daughter, Janet Drake, named for her aunt (who herself married James Ellsworth de Kay in 1821).

Eckford’s fame as a shipbuilder being well known, he accepted a position as chief naval constructor at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Besides shipbuilding, Eckford served in the New York State Legislature, ran for Congress, and was involved in a scandal with Tammany Hall. Eckford was never convicted of any crime, but he did demand a public apology from the New York District Attorney Hugh Maxwell. When the apology never came, Eckford challenged Maxwell to a duel but was ignored. Eckford soon went back to private shipbuilding, building the aforementioned United States.[vi]

III.

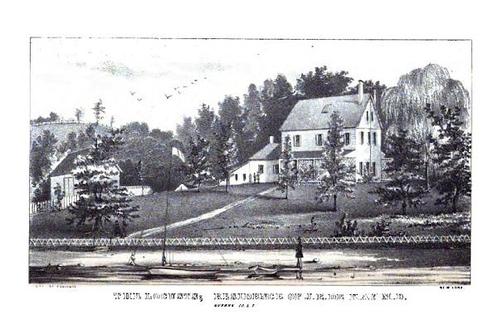

The Locusts, Oyster Bay Home of James Ellsworth de Kay

The Commodore, after bringing back Eckford’s remains for burial at St. George’s Church, married Janet Drake, Eckford’s granddaughter, in 1833. Their offspring included Catherine (1834), Joseph Rodman Drake (1836), Julia (1841), George Coleman (1843), Sydney (1845), Helena (1846) and Charles de Kay (1848). The Commodore and his wife settled in New Jersey near the Hudson River, while his brother James Ellsworth and his young family resided in Oyster Bay. These were times of leisure for him, and most likely their families visited each other often.

In the mid-1840s, a crisis overwhelmed the poor people of Ireland. A potato blight had destroyed the crop both in Ireland and Scotland, and thousands of Irishmen and Scots were dying of starvation. The Commodore, now 45 years old, remembered his Irish roots and was alarmed about this devastation. The American people had sent relief ships to Ireland with food but they were few in number and carried limited supplies. The Commodore, who was a man of action, petitioned Congress for a mid-sized warship to assist in the relief effort. In the spring of 1847, the Commodore’s request was granted by an act of Congress, and he was given the frigate Macedonian. Under the same act, another ship, the smaller Jamestown, went to Captain Forbes of Boston. This is the only time in the history of the United States that any warships went on loan to private parties.[vii]

Through the generosity of the American people, the Jamestown was loaded with food and other supplies and left Boston, returning from Ireland before the Commodore’s ship was ready. After Captain Forbes returned, he went to New York to assist the Commodore, who was delayed with a number of problems. The Navy had pulled the guns off the Macedonian but it had to be refitted, with a crew (hired at the Commodore’s expense), food, and other supplies to be readied. On June 19th, 1847, the winds caught the sails of the Macedonian[viii] and 27 days later she arrived in Cork, Ireland. After its three port relief visits in both Ireland and Scotland, the Commodore had dropped off over 12,000 barrels of foodstuffs, reportedly saving 9,000 Irish lives and improving the lot of nearly 25,000 others.[ix] Because of the loss of ballast on the Macedonian, the Commodore again spent his own money to ensure a safe voyage home to New York.

The Commodore now had spent close to $30,000 dollars towards the relief voyage to the Irish and Scottish people. In 1848 he moved his family to Washington, D. C. and requested reimbursement from Congress. The toll and strain of these negotiations most likely caused his death in the winter of 1849. The Commodore’s body was transported back to Long Island, to St. George’s Cemetery, where at the de Kay family plot he was finally laid to rest. The Commodore’s wife and children then moved up from Washington to The Locusts, where brother James made his home at Oyster Bay.

James Ellsworth de Kay (1792-1851), was the older brother of the Commodore and shared some of his adventures. He was born in Lisbon, Portugal, where his father, sea captain George de Kay, met his mother Katherine. Young James attended Yale for a few years but did not graduate. Later taking up an interest in medicine, he graduated as a physician from Edinburgh University, Scotland, in 1819.

James neglected his medical profession for some time, concentrating on the natural sciences. In 1825, he correctly identified the fossil Eurypterus remipes, which later became the official New York State fossil now on display at the New York State Museum in Albany. Traveling to Turkey in 1831 with his father-in-law, Henry Eckford, he later wrote a book about the area titled Sketches of Turkey, published in 1832. After his experiences in Turkey with cholera, James took up medicine in New York City, traveling from his home in Oyster Bay to prevent a cholera epidemic that was sweeping the city. James recommended port as a preventive drink, earning him the nickname Dr. Port. Years later, patrons in the saloons of the city would still ask for a Doctor de Kay as a drink.[x]

James bought a house off Cove Road, facing Oyster Bay Harbor, where he lived from the 1830s up until his death in 1851. In 1835 James and his neighbor Daniel Fleet built a pier dock on the harbor. The family dwelling, The Locusts, stood proudly there until it burned down in 1931.

James, active in the natural sciences, was a founder of the Lyceum of Natural History. When New York State wanted to complete a geological survey of the state, officials selected him to write the zoology and botany sections. It took James ten years to find and identify over 1,600 species of state fauna. James traveled around New York State and furthered his research by identifying additional animals and plants that bordered the state. His complete findings, published and illustrated in five volumes, was titled De Kay’s Zoology of New York; or The New York Fauna. James never rested in his quest for knowledge and even wrote to county clerks in search of the Native American place names in their vicinity. This information was never published but used in other books later to identify the meaning of such geographical and municipal names. This was valuable information, especially on Long Island. James survived his brother by only two years, dying at Oyster Bay and leaving a wife and three grown children. He was buried at St. George’s Cemetery.

In the mid-1840s, a crisis overwhelmed the poor people of Ireland. A potato blight had destroyed the crop both in Ireland and Scotland, and thousands of Irishmen and Scots were dying of starvation. The Commodore, now 45 years old, remembered his Irish roots and was alarmed about this devastation. The American people had sent relief ships to Ireland with food but they were few in number and carried limited supplies. The Commodore, who was a man of action, petitioned Congress for a mid-sized warship to assist in the relief effort. In the spring of 1847, the Commodore’s request was granted by an act of Congress, and he was given the frigate Macedonian. Under the same act, another ship, the smaller Jamestown, went to Captain Forbes of Boston. This is the only time in the history of the United States that any warships went on loan to private parties.[vii]

Through the generosity of the American people, the Jamestown was loaded with food and other supplies and left Boston, returning from Ireland before the Commodore’s ship was ready. After Captain Forbes returned, he went to New York to assist the Commodore, who was delayed with a number of problems. The Navy had pulled the guns off the Macedonian but it had to be refitted, with a crew (hired at the Commodore’s expense), food, and other supplies to be readied. On June 19th, 1847, the winds caught the sails of the Macedonian[viii] and 27 days later she arrived in Cork, Ireland. After its three port relief visits in both Ireland and Scotland, the Commodore had dropped off over 12,000 barrels of foodstuffs, reportedly saving 9,000 Irish lives and improving the lot of nearly 25,000 others.[ix] Because of the loss of ballast on the Macedonian, the Commodore again spent his own money to ensure a safe voyage home to New York.

The Commodore now had spent close to $30,000 dollars towards the relief voyage to the Irish and Scottish people. In 1848 he moved his family to Washington, D. C. and requested reimbursement from Congress. The toll and strain of these negotiations most likely caused his death in the winter of 1849. The Commodore’s body was transported back to Long Island, to St. George’s Cemetery, where at the de Kay family plot he was finally laid to rest. The Commodore’s wife and children then moved up from Washington to The Locusts, where brother James made his home at Oyster Bay.

James Ellsworth de Kay (1792-1851), was the older brother of the Commodore and shared some of his adventures. He was born in Lisbon, Portugal, where his father, sea captain George de Kay, met his mother Katherine. Young James attended Yale for a few years but did not graduate. Later taking up an interest in medicine, he graduated as a physician from Edinburgh University, Scotland, in 1819.

James neglected his medical profession for some time, concentrating on the natural sciences. In 1825, he correctly identified the fossil Eurypterus remipes, which later became the official New York State fossil now on display at the New York State Museum in Albany. Traveling to Turkey in 1831 with his father-in-law, Henry Eckford, he later wrote a book about the area titled Sketches of Turkey, published in 1832. After his experiences in Turkey with cholera, James took up medicine in New York City, traveling from his home in Oyster Bay to prevent a cholera epidemic that was sweeping the city. James recommended port as a preventive drink, earning him the nickname Dr. Port. Years later, patrons in the saloons of the city would still ask for a Doctor de Kay as a drink.[x]

James bought a house off Cove Road, facing Oyster Bay Harbor, where he lived from the 1830s up until his death in 1851. In 1835 James and his neighbor Daniel Fleet built a pier dock on the harbor. The family dwelling, The Locusts, stood proudly there until it burned down in 1931.

James, active in the natural sciences, was a founder of the Lyceum of Natural History. When New York State wanted to complete a geological survey of the state, officials selected him to write the zoology and botany sections. It took James ten years to find and identify over 1,600 species of state fauna. James traveled around New York State and furthered his research by identifying additional animals and plants that bordered the state. His complete findings, published and illustrated in five volumes, was titled De Kay’s Zoology of New York; or The New York Fauna. James never rested in his quest for knowledge and even wrote to county clerks in search of the Native American place names in their vicinity. This information was never published but used in other books later to identify the meaning of such geographical and municipal names. This was valuable information, especially on Long Island. James survived his brother by only two years, dying at Oyster Bay and leaving a wife and three grown children. He was buried at St. George’s Cemetery.

IV.

Helena de Kay Gilder

The Commodore’s young family lived in Oyster Bay a few more years until they too scattered to further their education, marry and earn a living. When the Civil War broke out, it found young George C. de Kay (1842-1862) engaged in his studies in Dresden, Germany. He came back to America and joined the Union Army. George was soon promoted to lieutenant, becoming the aid-de-camp to General Williams in the Delta campaign. In a skirmish at Grand Gulf, young George de Kay was fatally wounded and brought back to Long Island to be buried besides the Commodore, his father.[xi] Another son, Joseph Rodham Drake de Kay (1836-1886), also served in the Civil War on the staffs of generals Mansfield, Pope and Hooker. Joseph was soon promoted to captain of the 14th infantry and during the Battle of the Wilderness was badly hurt. He was discharged as a lieutenant colonel. After the war Joseph became an ardent Republican, forming the Boys in Blue Society. Joseph’s grave is also in the family plot at St. Georges.

The Commodore’s third son to enter the army was Sidney de Kay (1845-1890), who was studying at the Yale Scientific School. In the second year of the conflict, Sidney dropped his studies and enlisted as a private in the Sixty-Ninth Regiment of the New York Volunteers. After his first battle Sidney was promoted to lieutenant, making major soon after the attack on Fort Fisher. At the end of the war, Sidney joined the Cretans (Greeks) against the Turks in a guerrilla campaign on Crete. After suffering severe wounds, he returned to America where he studied law at Columbia University. Sidney later married and practiced law in Staten Island before he died at 50.[xii]

The Commodore’s youngest son was Charles de Kay (1849-1935).[xiii] Charles was born in Washington D. C. and lived in Oyster Bay with his brothers and sisters before his mother took them all to Europe in the mid 1850s. Charles was too young to join in the fight to preserve the union and instead went to Yale, graduating in 1868. Charles was an energetic young man who founded the New York Fencer’s Club in 1880, the Author’s Club in 1882, the National Sculpture Society in 1892, and the still extant National Arts Club (1898) in Gramercy Park. Charles became the literary editor of the New York Times (1876-94), where he wrote about promising artists, promoting the work of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. When President Cleveland appointed Charles Consul General to Berlin, Charles and his wife Edwardlyn (Coffey) and family were off to Germany. Charles wrote books, artistic critiques, and literary viewpoints for the rest of his long life and was one the first literary figures to have a summer home in East Hampton (1894-1935). Charles had the poetry genes of his grandfather, Joseph Drake, in him, for he wrote four volumes of poetry in the 1880s. His daughter, Phyllis, later married the great Long Island poet, John Hall Wheelock. Robert Underwood Johnson, former Chancellor of New York University said about him- “He was master of more branches of knowledge than any man I ever met-art, science, philology, oriental lore, general literature. He was not only intellectual but the master of half a dozen languages and a rare scholarly precision of statement.” [xiv]The graves of Charles and his wife Edwardlyn are at the family plot at St. George’s.

The Commodore’s three daughters—Katherine, Julia and Helena—also led interesting lives. Katherine married Arthur Bronson, a man of some wealth, living in Europe, New York City, and Newport, Rhode Island. Most of their lives were spent in high society, with Robert Browning and Henry James as personal friends. Julia de Kay (1841-1922), never married but became a translator and writer, living to be 82. The most publicized daughter was Helena, a beautiful woman who, with her husband Richard Watson Gilder and her brother Charles de Kay, was a fixture of the art scene in America for decades.

Helena de Kay (1846-1916), as an infant accompanied her parents on the Macedonian relief trip to Ireland.[xv] After living in Oyster Bay following her father’s death, Helena went with her family to Europe before the Civil War started. Returning after the war, Helena attended art classes at Cooper Union and received private lessons from Winslow Homer, who was said to be infatuated by her and used her likeness in a number of his paintings. But it was the promising editor and writer Richard Watson Gilder who would win her heart. Richard had served in the Civil War, and like her brothers also had Long Island roots. He attended a seminary in Flushing run by his father. Helena and Richard were married in 1874 and seven years later, Richard became the editor of Century Magazine, one of the most influential journals in America.

Richard’s fist volume of poetry bore a cover designed by his wife Helena. Both of them formed societies aimed at advancing the arts. Richard became one of the founders of the Author’s Club and the Society of American Architects, among others. Helena became one of the founders of the Art Student League and the Society of American Artists. Both of them were familiar with the leading writers and artists of their day. The sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens made a celebrated plaster sculpture of their young family. Their son, Rodman de Kay Gilder (1877-1953), was also an author and married Comfort Tiffany, a daughter of Louis Comfort Tiffany.[xvi]

George and Ormonde de Kay, two of the Commodore’s great-grandsons, also rest in peace at the St. George’s Cemetery, Ormonde, born in New York City and a graduate of Harvard University, was a writer, editor, poet and translator, serving in the United States Navy during W.W. II and on Navy destroyer escorts during the Korean War. He was a contributor to the script for the 1949 film Lost Boundaries and later wrote several children’s books, including a French translation of Mother Goose.[xvii]

The Commodore’s third son to enter the army was Sidney de Kay (1845-1890), who was studying at the Yale Scientific School. In the second year of the conflict, Sidney dropped his studies and enlisted as a private in the Sixty-Ninth Regiment of the New York Volunteers. After his first battle Sidney was promoted to lieutenant, making major soon after the attack on Fort Fisher. At the end of the war, Sidney joined the Cretans (Greeks) against the Turks in a guerrilla campaign on Crete. After suffering severe wounds, he returned to America where he studied law at Columbia University. Sidney later married and practiced law in Staten Island before he died at 50.[xii]

The Commodore’s youngest son was Charles de Kay (1849-1935).[xiii] Charles was born in Washington D. C. and lived in Oyster Bay with his brothers and sisters before his mother took them all to Europe in the mid 1850s. Charles was too young to join in the fight to preserve the union and instead went to Yale, graduating in 1868. Charles was an energetic young man who founded the New York Fencer’s Club in 1880, the Author’s Club in 1882, the National Sculpture Society in 1892, and the still extant National Arts Club (1898) in Gramercy Park. Charles became the literary editor of the New York Times (1876-94), where he wrote about promising artists, promoting the work of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. When President Cleveland appointed Charles Consul General to Berlin, Charles and his wife Edwardlyn (Coffey) and family were off to Germany. Charles wrote books, artistic critiques, and literary viewpoints for the rest of his long life and was one the first literary figures to have a summer home in East Hampton (1894-1935). Charles had the poetry genes of his grandfather, Joseph Drake, in him, for he wrote four volumes of poetry in the 1880s. His daughter, Phyllis, later married the great Long Island poet, John Hall Wheelock. Robert Underwood Johnson, former Chancellor of New York University said about him- “He was master of more branches of knowledge than any man I ever met-art, science, philology, oriental lore, general literature. He was not only intellectual but the master of half a dozen languages and a rare scholarly precision of statement.” [xiv]The graves of Charles and his wife Edwardlyn are at the family plot at St. George’s.

The Commodore’s three daughters—Katherine, Julia and Helena—also led interesting lives. Katherine married Arthur Bronson, a man of some wealth, living in Europe, New York City, and Newport, Rhode Island. Most of their lives were spent in high society, with Robert Browning and Henry James as personal friends. Julia de Kay (1841-1922), never married but became a translator and writer, living to be 82. The most publicized daughter was Helena, a beautiful woman who, with her husband Richard Watson Gilder and her brother Charles de Kay, was a fixture of the art scene in America for decades.

Helena de Kay (1846-1916), as an infant accompanied her parents on the Macedonian relief trip to Ireland.[xv] After living in Oyster Bay following her father’s death, Helena went with her family to Europe before the Civil War started. Returning after the war, Helena attended art classes at Cooper Union and received private lessons from Winslow Homer, who was said to be infatuated by her and used her likeness in a number of his paintings. But it was the promising editor and writer Richard Watson Gilder who would win her heart. Richard had served in the Civil War, and like her brothers also had Long Island roots. He attended a seminary in Flushing run by his father. Helena and Richard were married in 1874 and seven years later, Richard became the editor of Century Magazine, one of the most influential journals in America.

Richard’s fist volume of poetry bore a cover designed by his wife Helena. Both of them formed societies aimed at advancing the arts. Richard became one of the founders of the Author’s Club and the Society of American Architects, among others. Helena became one of the founders of the Art Student League and the Society of American Artists. Both of them were familiar with the leading writers and artists of their day. The sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens made a celebrated plaster sculpture of their young family. Their son, Rodman de Kay Gilder (1877-1953), was also an author and married Comfort Tiffany, a daughter of Louis Comfort Tiffany.[xvi]

George and Ormonde de Kay, two of the Commodore’s great-grandsons, also rest in peace at the St. George’s Cemetery, Ormonde, born in New York City and a graduate of Harvard University, was a writer, editor, poet and translator, serving in the United States Navy during W.W. II and on Navy destroyer escorts during the Korean War. He was a contributor to the script for the 1949 film Lost Boundaries and later wrote several children’s books, including a French translation of Mother Goose.[xvii]

FOOTNOTES

[i] Newsday, Alisha Al-Muslim, Irish group to honor 19th century resident. 06/16/11

[ii] The Commodore was written about in Fritz-Greene Halleck’s Outline of the life of Commodore George C. De Kay, in 1847. The Brooklyn Eagle also had many short articles about him and the voyage of the Macedonian.

[iii] The Commodore even had a fine uniform made up for him to go along with his new rank.

[iv] The town council of North Ayrshire, Scotland calls Henry Eckford “the father of the U.S. Navy.” Wikipedia.org, footnote 15.

[v] Another version states that Drake said to de Kay “They are nothing, burn them.”

[vi] Eckford’s legacy is remembered in many ways. A street in Brooklyn is named after him and several baseball teams in the 19th century took the name of Eckford, the first being made up of former shipwrights Also in New York State the Eckford chain of lakes in the Adirondacks is named after him.

[vii] These ships were given to them by Congress resolution number 6. New Hampshire Patriot, 04/22/1847.

[viii] For the full history of the frigate Macedonian refer to Chronicles of the Frigate Macedonian 1809-1922 by James Tertius de Kay. W.W. Norton, N.Y. 1995. The Macedonian was originally captured from the British in the War of 1812 by Commodore Decatur. June 19th was the date of the sailing in de Kay’s book, the Brooklyn Eagle listed it as June 17th. I suspect the ship was in the harbor testing her sails before leaving for Ireland.

[ix] These figures were from an article on the Macedonian in the Brooklyn Eagle, 10/29/1847. P.2

[x] James was assisted by Dr. Rhinelander who recommended to New Yorkers to drink brandy. Thus years later they would ask also for a Doctor Rhinelander at the saloons.

[xi] The New York Times, The Skirmish at Grand Gulf. 06/15/1862.

[xii] The New York Times, Sidney de Kay, obituary. 08/31/1890, pg5. It is also written that the King of Greece thanked him for his service.

[xiii] I was first searching for Charles de Kay’s gravesite which was not known either by Yale University or The National Arts Club. From this “finding” his family history was revealed to me.

[xiv] The New York Times, Charles de Kay, 86, poet, Critic, Dead. Obituary, 05/24/1935.

[xv] A Brooklyn Eagle article insinuated this and his great grand-son, James T. de Kay, agreed to this fact.

[xvi] The most comprehensive information on Helena de Kay Gilder can be found at Dan McNay’s web site- helenakaygilder.org

[xvii] The New York Times. Ormonde de Kay, 74, Writer, Poet, Editor and Translator. Obituary, Arts section.

With thanks to James T. de Kay, Dorothy Harrison, Dan McNay and Ellen Schutt who gave either their time or information to make this article possible.

The Syosset Farmer Who Would Have Shot Theodore Roosevelt?

Sagamore Hill

by Tom Montalbano

Twenty-eight-year-old Henry Weilbrenner, Jr. was the son of a German immigrant “truck farmer” who owned a 72-acre parcel of land on the west side of Jackson Avenue, encompassing what is now De Benedittis Nursery and the surrounding area. One of three brothers, Henry played a significant role in his family’s daily grind, which included hauling a large, horse-drawn wagon (truck) into Brooklyn or Manhattan each day to hawk fresh produce to restaurant owners, cruise ship purchasing agents, and servants to Manhattan’s elite. To balance the tedium and stress of his day-to-day routine, Henry apparently manufactured an imaginary love affair with Alice Roosevelt, the daughter of the 26th President of the United States, for whom the fantasy almost turned deadly.

A Young Man Falls In Love

Truck farming was a grueling life that could take a heavy toll on a man’s nerves. For the Weilbrenners of Syosset, life had become even more difficult at the onset of the twentieth century, as they had fallen into debt on their farm and had spent the next few years struggling to hold on to their investment. For Henry Weilbrenner, Jr., namesake of the farm owner, the pressure was sometimes debilitating.

At one point, Henry Jr. suffered what his family described as a “nervous attack which rendered him mentally helpless for a day or two.” However, the Weilbrenner family believed that medical treatment he had received at the time had cured him, as he had managed to keep up with his farm duties and stay out of trouble around Syosset for a number of years.

Unbeknownst to his family, in his mid-twenties, Henry Jr. developed an infatuation with Miss Alice Roosevelt, the very attractive daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt, who maintained a “Summer White House” at Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, commonly visited Syosset to use the railroad station or to chat with friends along Jackson Avenue. Alice, a product of Roosevelt’s first marriage, had risen to celebrity status both for her bold fashion sense and her “bad girl” behavior. In what family members described as an attempt to win her father’s attention, Alice constantly went out of her way to break common social rules for woman, smoking cigarettes in public, staying out late partying, and even placing bets with a bookie. At one point during his presidency, TR was heard to declare "I can either run the country or I can attend to Alice, but I cannot possibly do both!" To some, Alice was a detriment to TR’s presidential image, but to a young, unsophisticated farmer such as Weilbrenner, her antics apparently stirred up quite a bit of excitement.

Twenty-eight-year-old Henry Weilbrenner, Jr. was the son of a German immigrant “truck farmer” who owned a 72-acre parcel of land on the west side of Jackson Avenue, encompassing what is now De Benedittis Nursery and the surrounding area. One of three brothers, Henry played a significant role in his family’s daily grind, which included hauling a large, horse-drawn wagon (truck) into Brooklyn or Manhattan each day to hawk fresh produce to restaurant owners, cruise ship purchasing agents, and servants to Manhattan’s elite. To balance the tedium and stress of his day-to-day routine, Henry apparently manufactured an imaginary love affair with Alice Roosevelt, the daughter of the 26th President of the United States, for whom the fantasy almost turned deadly.

A Young Man Falls In Love

Truck farming was a grueling life that could take a heavy toll on a man’s nerves. For the Weilbrenners of Syosset, life had become even more difficult at the onset of the twentieth century, as they had fallen into debt on their farm and had spent the next few years struggling to hold on to their investment. For Henry Weilbrenner, Jr., namesake of the farm owner, the pressure was sometimes debilitating.

At one point, Henry Jr. suffered what his family described as a “nervous attack which rendered him mentally helpless for a day or two.” However, the Weilbrenner family believed that medical treatment he had received at the time had cured him, as he had managed to keep up with his farm duties and stay out of trouble around Syosset for a number of years.

Unbeknownst to his family, in his mid-twenties, Henry Jr. developed an infatuation with Miss Alice Roosevelt, the very attractive daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt, who maintained a “Summer White House” at Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, commonly visited Syosset to use the railroad station or to chat with friends along Jackson Avenue. Alice, a product of Roosevelt’s first marriage, had risen to celebrity status both for her bold fashion sense and her “bad girl” behavior. In what family members described as an attempt to win her father’s attention, Alice constantly went out of her way to break common social rules for woman, smoking cigarettes in public, staying out late partying, and even placing bets with a bookie. At one point during his presidency, TR was heard to declare "I can either run the country or I can attend to Alice, but I cannot possibly do both!" To some, Alice was a detriment to TR’s presidential image, but to a young, unsophisticated farmer such as Weilbrenner, her antics apparently stirred up quite a bit of excitement.

An Unconventional Marriage Proposal

Theodore Roosevelt and family

Weilbrenner’s obsession crossed the line late in the evening of September 1, 1903, when he arrived by horse and buggy at the gate of Sagamore Hill dressed in a dapper black suit and an old-fashioned derby hat and advised the Secret Service operative that he had a “personal engagement” with the president. The agent, accustomed to turning away aggressive newspaper reporters and star-gazers, tactfully advised Weilbrenner that 10:00pm was long past the hours when the president normally accepted visitors and that he could not let him through the gate. Weilbrenner persisted somewhat, but eventually turned his carriage around and rode away.

A short while later, Weilbrenner returned and insisted that he be allowed to see the president, if only for a minute. After refusing several times to answer why he needed to see the president, Weilbrenner reportedly snapped “None of your damned business!” This time, the Secret Service agent ordered him away from the property and warned him not to return.

The agent’s directive apparently did not dissuade Weilbrenner for very long. At approximately 11:00pm, as Roosevelt finished some work in his study, Weilbrenner appeared for a third time and demanded that he be permitted to see the president, “at once!” When the agent again refused him, Weilbrenner proceeded to create a commotion that drew the president out to his porch, less than 100 yards from the gate.

Upon glimpsing the president, Weilbrenner whipped up his horse as if to make a dash for the house. Instinctively, the agent jumped on the buggy, dragged Weilbrenner over the front wheels and brought him to the ground. As the president ran back into the house, the agent subdued Weilbrenner and hauled him to a barn on the property. There, he placed him under the armed watch of two stablemen while he secured the president’s home and searched Weilbrenner’s wagon, in which he found a fully loaded revolver.

Alarmed that the President of the United States might be under attack, the agent summoned five additional Secret Service operatives who were lodging at the Octagon Hotel in Oyster Bay. Upon arrival by horseback, the team conducted a full search of the grounds and the surrounding area, but found no evidence of accomplices. They then removed Weilbrenner from the stable and transported him, via a special Long Island Rail Road car, to the County Jail in Mineola, where he was locked up overnight.

A short while later, Weilbrenner returned and insisted that he be allowed to see the president, if only for a minute. After refusing several times to answer why he needed to see the president, Weilbrenner reportedly snapped “None of your damned business!” This time, the Secret Service agent ordered him away from the property and warned him not to return.

The agent’s directive apparently did not dissuade Weilbrenner for very long. At approximately 11:00pm, as Roosevelt finished some work in his study, Weilbrenner appeared for a third time and demanded that he be permitted to see the president, “at once!” When the agent again refused him, Weilbrenner proceeded to create a commotion that drew the president out to his porch, less than 100 yards from the gate.

Upon glimpsing the president, Weilbrenner whipped up his horse as if to make a dash for the house. Instinctively, the agent jumped on the buggy, dragged Weilbrenner over the front wheels and brought him to the ground. As the president ran back into the house, the agent subdued Weilbrenner and hauled him to a barn on the property. There, he placed him under the armed watch of two stablemen while he secured the president’s home and searched Weilbrenner’s wagon, in which he found a fully loaded revolver.

Alarmed that the President of the United States might be under attack, the agent summoned five additional Secret Service operatives who were lodging at the Octagon Hotel in Oyster Bay. Upon arrival by horseback, the team conducted a full search of the grounds and the surrounding area, but found no evidence of accomplices. They then removed Weilbrenner from the stable and transported him, via a special Long Island Rail Road car, to the County Jail in Mineola, where he was locked up overnight.

Inside The Mind of a “Demented Farmer”

Octagon Hotel in Oyster Bay

At his arraignment at the Nassau County Court the following day, Weilbrenner remained calm and collected as he explained the reason for his visit to Sagamore Hill.

“I went to see the president about his daughter.” Weilbrenner stated, matter-of-factly.

Asked if he had an appointment with the president, Weilbrenner responded “Yes. I talked with the president last night.” Questioned as to how he contacted the president, Weilbrenner answered “Oh, I just talked.”

The investigating officer then asked Weilbrenner if his family owned a telephone, to which he responded, “No.” At this point, the officer remarked, perhaps mockingly, “A sort of ‘wireless’ talk then, was it?”, evidently referring to the new wireless communication technology that had recently been adopted by the US Navy.

“Yes. That is it…a wireless talk,” replied Weilbrenner, who went on to explain that he and the president could talk to one another from their respective houses without the assistance of a telephone, telegraph, or radio system of any type.

“And why did you want to see the president about Miss Alice?” the examiner continued.

“Because I wanted to marry her,” stated a perfectly composed Weilbrenner.

Asked if he had ever met Alice Roosevelt, Weilbrenner advised that he had known her for about six months and that she had visited him at his house in Syosset the previous night, having driven up in a red automobile with her brother, Theodore, Jr.

Questioned as to why he was carrying a fully loaded gun when he went to see the president, Weilbrenner stated that he had been practicing his marksmanship recently, but could give no reason why. He also advised that he wasn’t a very good shot.

When it became apparent that Weilbrenner might be mentally deranged, the examiner called the prisoner’s mother, brother, and sister in for questioning. The family members told investigators that Henry Jr. had been moody recently and that, with the president and his family constantly before the public, he had become obsessed with them.

Although Weilbrenner never claimed that he intended to kill the president, the headlines of many big city newspapers reported this to be the case, describing him as the “demented Syosset farmer” and a “dangerous lunatic” who “sought the president with a loaded revolver.”

The following day, Drs. George Stewart and Irving Barnes interviewed Weilbrenner, declared him to be insane and unfit to stand trial for an attempt on the life of the president, and immediately committed him to the Kings Park Asylum.

Although Roosevelt, in speaking with the press in the days that followed, described Weilbrenner as a “poor, demented creature,” a family member later quoted him as remarking in private “Of course he’s insane…he wants to marry Alice!”

“I went to see the president about his daughter.” Weilbrenner stated, matter-of-factly.

Asked if he had an appointment with the president, Weilbrenner responded “Yes. I talked with the president last night.” Questioned as to how he contacted the president, Weilbrenner answered “Oh, I just talked.”

The investigating officer then asked Weilbrenner if his family owned a telephone, to which he responded, “No.” At this point, the officer remarked, perhaps mockingly, “A sort of ‘wireless’ talk then, was it?”, evidently referring to the new wireless communication technology that had recently been adopted by the US Navy.

“Yes. That is it…a wireless talk,” replied Weilbrenner, who went on to explain that he and the president could talk to one another from their respective houses without the assistance of a telephone, telegraph, or radio system of any type.

“And why did you want to see the president about Miss Alice?” the examiner continued.

“Because I wanted to marry her,” stated a perfectly composed Weilbrenner.

Asked if he had ever met Alice Roosevelt, Weilbrenner advised that he had known her for about six months and that she had visited him at his house in Syosset the previous night, having driven up in a red automobile with her brother, Theodore, Jr.

Questioned as to why he was carrying a fully loaded gun when he went to see the president, Weilbrenner stated that he had been practicing his marksmanship recently, but could give no reason why. He also advised that he wasn’t a very good shot.

When it became apparent that Weilbrenner might be mentally deranged, the examiner called the prisoner’s mother, brother, and sister in for questioning. The family members told investigators that Henry Jr. had been moody recently and that, with the president and his family constantly before the public, he had become obsessed with them.

Although Weilbrenner never claimed that he intended to kill the president, the headlines of many big city newspapers reported this to be the case, describing him as the “demented Syosset farmer” and a “dangerous lunatic” who “sought the president with a loaded revolver.”

The following day, Drs. George Stewart and Irving Barnes interviewed Weilbrenner, declared him to be insane and unfit to stand trial for an attempt on the life of the president, and immediately committed him to the Kings Park Asylum.

Although Roosevelt, in speaking with the press in the days that followed, described Weilbrenner as a “poor, demented creature,” a family member later quoted him as remarking in private “Of course he’s insane…he wants to marry Alice!”

Life Goes On

Roosevelt at Oyster Bay Train Station, August 1901

Theodore Roosevelt continued to visit Syosset and to use the train station on Jackson Avenue despite the incident involving Weilbrenner, whose family auctioned off their Jackson Avenue farm and left Syosset shortly afterward.

In 1906, Miss Alice married Congressman Nicholas Longworth of Cincinnati in what has been described as the “grandest White House wedding of all” and “the most spectacular social event in all of American History.” Six years later, Roosevelt was shot and wounded by a saloonkeeper while campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

On his return to Sagamore Hill to recover from the shooting, Roosevelt fooled the hordes of reporters at the Oyster Bay station by secretly arriving in Syosset instead.

Tom Montalbano is the author of Syosset: Images of America, the first of two photographic histories of Syosset, as well as Steel Rails through the Pines: The First 150 Years of the Syosset Train Station, an e-book that can be downloaded free at www.SyossetChamber.com. He is currently compiling a history of the Syosset Fire Department in honor of its 100th Anniversary in 2015.

In 1906, Miss Alice married Congressman Nicholas Longworth of Cincinnati in what has been described as the “grandest White House wedding of all” and “the most spectacular social event in all of American History.” Six years later, Roosevelt was shot and wounded by a saloonkeeper while campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

On his return to Sagamore Hill to recover from the shooting, Roosevelt fooled the hordes of reporters at the Oyster Bay station by secretly arriving in Syosset instead.

Tom Montalbano is the author of Syosset: Images of America, the first of two photographic histories of Syosset, as well as Steel Rails through the Pines: The First 150 Years of the Syosset Train Station, an e-book that can be downloaded free at www.SyossetChamber.com. He is currently compiling a history of the Syosset Fire Department in honor of its 100th Anniversary in 2015.

Proudly powered by Weebly