Long Island Flyboys, Part I: The Lafayette Escadrille

by Robert L. Harrison

From the start of the First World War in 1914, many Americans joined the French ambulance services transporting thousands of wounded soldiers to hospitals and aid stations, while others saw action by serving in the French Foreign Legion. These volunteers in the foreign service maintained their American citizenship through a treaty enabling them to serve in defense of France. It was a costly defense, as the casualty rate at Verdun and Champagne at times exceeded 70% for those who fought. Conditions were a living hell, with the cold, the lice, the constant shelling. The opportunity to learn to fly and fight above the trenches led many men to transfer to the French Aviation Corps. Little did they know of the new dangers ahead.

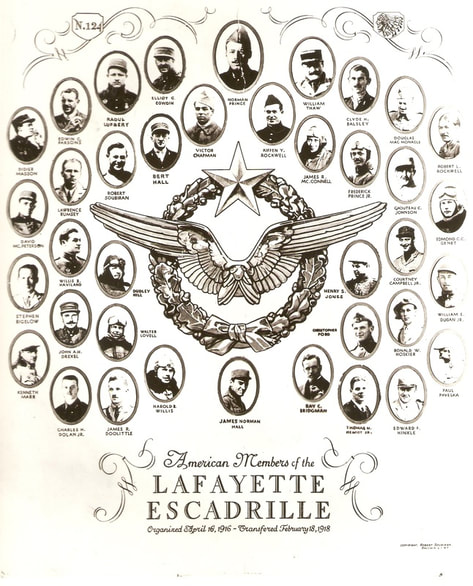

In the fall of 1915, Dr. Edmund Gros, in charge of the American Field Hospital in Paris, met with Norman Prince and William Thaw, both American aviators in French units. The meeting led to the formation of an all-American squadron to fight the Germans. By the spring of 1916, the Escadrille Americaine was formed. Because America was not at war with Germany, the Germans protested the unit’s designation, which was in December changed to the Escadrille Lafayette (Nieuport 124). This squadron, led exclusively by French officers, saw only 38 American pilots in service over its brief lifetime. Other French aviation units accepted American volunteers and became known as the Lafayette Flying Corps. Together, they saw 269 Americans in service, many from the New York metropolitan area, and sixteen from Long Island alone. This new Escadrille was backed financially by W.K Vanderbilt (1849-1920) who had family roots both in Northport and Oakdale. Two other Long Islanders, J. P. Morgan and August Belmont were supporters of our aviators in France. Vanderbilt would be awarded later the Legion of Honor for his efforts by the French government.

The hazards of air warfare quickly became apparent to American aviators. The French provided up to seven months of ground training before pilots were graded for solo flight. But the French Nieuport and Spad biplanes had many faults. Sometimes parts of the plane would fall off in a dive, or the engine would stall out, bringing the pilot down to his death. The first machine guns had fewer than fifty rounds and jammed often. To unjam the gun each pilot flew with a hammer to bang the faulty weapon while flying one-handed. Early on, there was only enough fuel for two hours of flying time, and many men undertook forced landings in farm fields, often behind enemy lines, while trying to return to base. Paper maps sometimes gave less than perfect directions, and most planes provided flew no cockpit heat, with some pilots suffering severe facial frostbite. The Lafayette Corps aviator Eugene Bullard routinely brought a pet monkey along under his leather jacket to keep him warm. High altitudes caused some men to faint and lose control of their aircraft. At first, pilots carried no parachutes on board. One pilot, to avoid the flames consuming his plane, climbed onto his wing and jumped off.

This is the two-part story of our sixteen brave Long Island flyboys—hailing from Baldwin, Cedarhurst, Old Westbury, Sea Cliff, Huntington, Patchogue, Bay Shore, Roslyn, Northport, Kensington, Quogue and Sheepshead Bay—who volunteered to fight for France before the United States entered the war in 1917. In total, they shot down more than eleven enemy aircraft. They received eleven Croix de Guerre, six Medaille Militaire, and three Legions of Honor from the French Government. After the war some joined Grumman, Sperry and Republic aircraft companies, while others became master polo players, mechanics, businessmen and shop keepers. Those that transferred to U.S. Army or Navy aviation units were later discharged at Garden City. Others undertook seaplane operations at Bay Shore and Rockaway Island stations.

Part I: Lafayette Escadrille

Elliot Christopher Cowdin (1886-1933)

Born in Far Rockaway, Long Island, Elliot Cowdin was the son of wealthy businessman John Elliot and Gertrude (Cheever) Cowdin. The families of both parents of were involved in sports, particularly polo.

After graduating from Harvard College in 1907, Cowdin went to France in 1914 to join the American Ambulance Services. The following year he transferred to the French Aviation Service, completing his air training in record time. In his first assignment he piloted bombers and flew in the battles of Champagne and Verdun, receiving the Croix de Guerre with Palm for his endeavors. In one engagement he fought off two German Taube aircraft, while under heavy fire. In the spring of 1916 he became one of the original members of the Escadrille Americaine. On July 4th 1916, as a pursuit pilot, he encountered the famous German Ace Hauptmann Boelcke. They fought until both pilots, their ammunition exhausted, returned to their respective bases. France later awarded Cowdin the Medaille Militare, (the first American pilot so honored). On leave, Cowdin came back to America to raise money during the Liberty Bond drives. After returning to France, he fell ill and saw limited action, before joining the U.S Air Service as a Major.

After the war and for the rest of his short life, Cowdin pursued the course of a retired gentleman. He never married and died in Palm Beach, Florida, of pneumonia at the age of 47. He is buried in the Cheever/Cowdin section of the St. John’s Episcopal Church Trinity Cemetery in Hewlett.

Sources: 1909 Harvard Yearbook. Lafayettefoundation.org. Obituary, the New York Times, 01/07/1933.

William Edward Dugan (1890-1924)

William Dugan was born in Patchogue on January 21, 1890. His father was a shoe manufacturer from Rochester. His mother, Sally Hudson, from a well-known Long Island sea-faring family, died when Dugan was only three years old. His grandfather was a sea captain who lived in the village near the bay at 28 Rider Avenue.

Dugan lived an adventurous and tragically short life. At the age of 19, he left the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to work as an engineer on the State Education Building in Albany. Bored with his work, young Dugan caught a tramp steamer bound for Panama. He jumped ship in Nicaragua, signing on the United Fruit Company. Three years later, after reading about the war in Europe, Dugan quit his job and boarded a steamer to Europe with the intention of fighting for France against the Germans.

Arriving in France, Dugan joined the French Foreign Legion and fought in some of the most savage battles of the war. He reminisced later about fighting in the trenches for a week straight and sleeping standing up holding his rife. In the battle of Champagne, Dugan’s regiment of one thousand men suffered an 80% casualty rate. Once declared missing in action, he was two days later found wounded on the battlefield. With the Lafayette Escadrille, he once found himself attacked by two German fighters before escaping to a remote British airfield. When America entered the war, Dugan was commissioned a First Lieutenant with the newly formed 103 Aero Pursuit Squadron. After completing 50 months of unwavering service in the defense of France, Dugan was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor.

After the war, Dugan returned to Central America as a manager for the United Fruit Company. Within just a few years, however, both his wife and new-born son died. In his grief, Dugan turned down any advancement in the company but did take an offer to explore the jungles south of the Panama Canal, setting off by canoe and foot over miles of difficult terrain. Falling sick himself, Dugan came back to Patchogue to see his grandmother, Martha Hudson, and seek treatment for his illness. He died in Patchogue Hospital of septicemia and was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx with his family.

Sources: United States Passport applications, 1921, 1924. American Fliers Missing in France, Dugan Missing. The New York Times, 09/10/1917. Bill Dugan Still Lives, The Daily Argus, 03/07/1918. P7. Governor and Attorney General to Do Honor to Rochester War Aviator, Rochester Democrat, 08/30/1917. P13. W.E. Dugan, Explorer, Victim of Septicemia. The New York Times, 09/05/1924. Pg. 24.

James Lovell (1884-1937)

James Lovell was born in Newton, Massachusetts, on September 9th 1884. He attended Harvard University and received his A.B. degree in 1907. Lovell sailed for France in 1914 to serve in the American Ambulance Service. He rose to become an Assistant Director of his sector and was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his heroic rescue of wounded French soldiers.

After service at the Verdun front he briefly joined the French Foreign Legion before becoming a member of the Lafayette Escadrille. Lovell’s flying adventures were many but he was only credited with downing two enemy aircraft. He engaged the Germans deep in their territory before flying back to base and landing with little or no gas. In air fights he once forced his German counterpart to ground, and in another dogfight, witnessed by troops on the field, he brought his adversary crashing down in flames. For his flying skills, Lovell was awarded a second Croix de Guerre for aviation. Then, after America entered the war, he joined the U.S. Aviation service, rising to the rank of Major.

Lovell stayed in France on business, accompanied by his wife, the former Helene de Bouchet. After a few years, Lovell came back to America and invested in the Suffolk Blue Coal and Ice Agency in Bay Shore, Long Island. In 1937, Lovell suffered a brain abscess and died in Southside Hospital in Bay Shore.

Sources: Obituary, Walter Lovell, War Flier, Dead. the New York Times, 09/10/1937. Pg. 23. Various web sites on the Lafayette Escadrille.

by Robert L. Harrison

From the start of the First World War in 1914, many Americans joined the French ambulance services transporting thousands of wounded soldiers to hospitals and aid stations, while others saw action by serving in the French Foreign Legion. These volunteers in the foreign service maintained their American citizenship through a treaty enabling them to serve in defense of France. It was a costly defense, as the casualty rate at Verdun and Champagne at times exceeded 70% for those who fought. Conditions were a living hell, with the cold, the lice, the constant shelling. The opportunity to learn to fly and fight above the trenches led many men to transfer to the French Aviation Corps. Little did they know of the new dangers ahead.

In the fall of 1915, Dr. Edmund Gros, in charge of the American Field Hospital in Paris, met with Norman Prince and William Thaw, both American aviators in French units. The meeting led to the formation of an all-American squadron to fight the Germans. By the spring of 1916, the Escadrille Americaine was formed. Because America was not at war with Germany, the Germans protested the unit’s designation, which was in December changed to the Escadrille Lafayette (Nieuport 124). This squadron, led exclusively by French officers, saw only 38 American pilots in service over its brief lifetime. Other French aviation units accepted American volunteers and became known as the Lafayette Flying Corps. Together, they saw 269 Americans in service, many from the New York metropolitan area, and sixteen from Long Island alone. This new Escadrille was backed financially by W.K Vanderbilt (1849-1920) who had family roots both in Northport and Oakdale. Two other Long Islanders, J. P. Morgan and August Belmont were supporters of our aviators in France. Vanderbilt would be awarded later the Legion of Honor for his efforts by the French government.

The hazards of air warfare quickly became apparent to American aviators. The French provided up to seven months of ground training before pilots were graded for solo flight. But the French Nieuport and Spad biplanes had many faults. Sometimes parts of the plane would fall off in a dive, or the engine would stall out, bringing the pilot down to his death. The first machine guns had fewer than fifty rounds and jammed often. To unjam the gun each pilot flew with a hammer to bang the faulty weapon while flying one-handed. Early on, there was only enough fuel for two hours of flying time, and many men undertook forced landings in farm fields, often behind enemy lines, while trying to return to base. Paper maps sometimes gave less than perfect directions, and most planes provided flew no cockpit heat, with some pilots suffering severe facial frostbite. The Lafayette Corps aviator Eugene Bullard routinely brought a pet monkey along under his leather jacket to keep him warm. High altitudes caused some men to faint and lose control of their aircraft. At first, pilots carried no parachutes on board. One pilot, to avoid the flames consuming his plane, climbed onto his wing and jumped off.

This is the two-part story of our sixteen brave Long Island flyboys—hailing from Baldwin, Cedarhurst, Old Westbury, Sea Cliff, Huntington, Patchogue, Bay Shore, Roslyn, Northport, Kensington, Quogue and Sheepshead Bay—who volunteered to fight for France before the United States entered the war in 1917. In total, they shot down more than eleven enemy aircraft. They received eleven Croix de Guerre, six Medaille Militaire, and three Legions of Honor from the French Government. After the war some joined Grumman, Sperry and Republic aircraft companies, while others became master polo players, mechanics, businessmen and shop keepers. Those that transferred to U.S. Army or Navy aviation units were later discharged at Garden City. Others undertook seaplane operations at Bay Shore and Rockaway Island stations.

Part I: Lafayette Escadrille

Elliot Christopher Cowdin (1886-1933)

Born in Far Rockaway, Long Island, Elliot Cowdin was the son of wealthy businessman John Elliot and Gertrude (Cheever) Cowdin. The families of both parents of were involved in sports, particularly polo.

After graduating from Harvard College in 1907, Cowdin went to France in 1914 to join the American Ambulance Services. The following year he transferred to the French Aviation Service, completing his air training in record time. In his first assignment he piloted bombers and flew in the battles of Champagne and Verdun, receiving the Croix de Guerre with Palm for his endeavors. In one engagement he fought off two German Taube aircraft, while under heavy fire. In the spring of 1916 he became one of the original members of the Escadrille Americaine. On July 4th 1916, as a pursuit pilot, he encountered the famous German Ace Hauptmann Boelcke. They fought until both pilots, their ammunition exhausted, returned to their respective bases. France later awarded Cowdin the Medaille Militare, (the first American pilot so honored). On leave, Cowdin came back to America to raise money during the Liberty Bond drives. After returning to France, he fell ill and saw limited action, before joining the U.S Air Service as a Major.

After the war and for the rest of his short life, Cowdin pursued the course of a retired gentleman. He never married and died in Palm Beach, Florida, of pneumonia at the age of 47. He is buried in the Cheever/Cowdin section of the St. John’s Episcopal Church Trinity Cemetery in Hewlett.

Sources: 1909 Harvard Yearbook. Lafayettefoundation.org. Obituary, the New York Times, 01/07/1933.

William Edward Dugan (1890-1924)

William Dugan was born in Patchogue on January 21, 1890. His father was a shoe manufacturer from Rochester. His mother, Sally Hudson, from a well-known Long Island sea-faring family, died when Dugan was only three years old. His grandfather was a sea captain who lived in the village near the bay at 28 Rider Avenue.

Dugan lived an adventurous and tragically short life. At the age of 19, he left the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to work as an engineer on the State Education Building in Albany. Bored with his work, young Dugan caught a tramp steamer bound for Panama. He jumped ship in Nicaragua, signing on the United Fruit Company. Three years later, after reading about the war in Europe, Dugan quit his job and boarded a steamer to Europe with the intention of fighting for France against the Germans.

Arriving in France, Dugan joined the French Foreign Legion and fought in some of the most savage battles of the war. He reminisced later about fighting in the trenches for a week straight and sleeping standing up holding his rife. In the battle of Champagne, Dugan’s regiment of one thousand men suffered an 80% casualty rate. Once declared missing in action, he was two days later found wounded on the battlefield. With the Lafayette Escadrille, he once found himself attacked by two German fighters before escaping to a remote British airfield. When America entered the war, Dugan was commissioned a First Lieutenant with the newly formed 103 Aero Pursuit Squadron. After completing 50 months of unwavering service in the defense of France, Dugan was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor.

After the war, Dugan returned to Central America as a manager for the United Fruit Company. Within just a few years, however, both his wife and new-born son died. In his grief, Dugan turned down any advancement in the company but did take an offer to explore the jungles south of the Panama Canal, setting off by canoe and foot over miles of difficult terrain. Falling sick himself, Dugan came back to Patchogue to see his grandmother, Martha Hudson, and seek treatment for his illness. He died in Patchogue Hospital of septicemia and was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx with his family.

Sources: United States Passport applications, 1921, 1924. American Fliers Missing in France, Dugan Missing. The New York Times, 09/10/1917. Bill Dugan Still Lives, The Daily Argus, 03/07/1918. P7. Governor and Attorney General to Do Honor to Rochester War Aviator, Rochester Democrat, 08/30/1917. P13. W.E. Dugan, Explorer, Victim of Septicemia. The New York Times, 09/05/1924. Pg. 24.

James Lovell (1884-1937)

James Lovell was born in Newton, Massachusetts, on September 9th 1884. He attended Harvard University and received his A.B. degree in 1907. Lovell sailed for France in 1914 to serve in the American Ambulance Service. He rose to become an Assistant Director of his sector and was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his heroic rescue of wounded French soldiers.

After service at the Verdun front he briefly joined the French Foreign Legion before becoming a member of the Lafayette Escadrille. Lovell’s flying adventures were many but he was only credited with downing two enemy aircraft. He engaged the Germans deep in their territory before flying back to base and landing with little or no gas. In air fights he once forced his German counterpart to ground, and in another dogfight, witnessed by troops on the field, he brought his adversary crashing down in flames. For his flying skills, Lovell was awarded a second Croix de Guerre for aviation. Then, after America entered the war, he joined the U.S. Aviation service, rising to the rank of Major.

Lovell stayed in France on business, accompanied by his wife, the former Helene de Bouchet. After a few years, Lovell came back to America and invested in the Suffolk Blue Coal and Ice Agency in Bay Shore, Long Island. In 1937, Lovell suffered a brain abscess and died in Southside Hospital in Bay Shore.

Sources: Obituary, Walter Lovell, War Flier, Dead. the New York Times, 09/10/1937. Pg. 23. Various web sites on the Lafayette Escadrille.

Frederick Henry Prince, Jr. (1885-1962)

Frederick Prince was born in Boston, Massachusetts, taking the name of his father Frederick Henry Prince, Sr., a wealthy banker and industrialist. Prince, taught by private tutors in France, also attended the Groton School and Harvard College, while his brother, Norman Prince, became a certified pilot and a founder of the Lafayette Escadrille.

In January 1916, Prince traveled to France, where he joined the Foreign Legion, later taking up aviation alongside his brother in the Escadrille Americaine. A week before Prince started his training, his brother Norman was killed while attempting to land following a combat mission. Prince took up the fight against the Germans and flew with the Escadrille and other units, figuring in twenty-two aerial engagements, for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

After returning to America in 1919, Prince pursued many business enterprises, spending his leisure on fox hunting, polo and yachting. He lived in Marshall, Virginia, and in Old Westbury with his wife, the former Virginia Mitchell. He died at the age of 76 at his home in Old Westbury, ever proud to be part of the great air adventure. His tombstone in the St. John’s Memorial Cemetery in Laurel Hollow bears the symbol of the Lafayette Escadrille.

Sources: Obituary, Frederick H. Prince Jr. Is Dead; Flew With Lafayette Escadrille. New York Times, 10/06/1962. Pg. 25. Various web sites. St. John’s Memorial Cemetery, Laurel Hollow.

Robert Soubiran (1886-1949)

Born in France, young Robert Soubiran immigrated with his parents to America. His first job was as a newspaper boy. At the Simplex Motor Company, he quickly advanced from mechanic to full- time racing car driver, competing in car races. At the outbreak of the Great War, Soubiran became one of the first American volunteers to join the French Foreign Legion.

In the second year of the war, Soubiran was wounded and hospitalized during the Champagne Offensive. After his recovery, he joined the Lafayette Escadrille and completed over 400 missions, flying for French and American aviation. In one action he was surrounded by four German aircraft, saved only by the heroic interference of another Lafayette pilot. His first score was recorded on Oct 17, 1917, though in a newspaper interview twenty years later, he claimed at least six more downed planes—an assertion more likely true than not, as French standards of accountability in matters of military engagement were so high.

While serving as a pilot Soubiran married Ann Marie Choudry and would later have three daughters by this union. Soubiran also became the unofficial photographer of the Escadrille and these historic photographs of their activities were donated to the Smithsonian Institute after his death by his wife. When America entered the war, Soubiran joined the 103rd Pursuit Squadron and rose to be its commanding officer. Before his honorable discharge as a Major, Soubiran was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor by the French government.

After the war, Soubiran served as a sales representative for Delco Manufacturing Company. Later in the 1920s he worked in France for General Motors until the deepening depression eliminated his position. On returning to the United States, he became general manager at one of Frederick Prince’s estates, settling down for the remainder of his life at 138 Kenneth Street in Baldwin.

The outbreak of World War II found Soubiran running his sister’s antique store at 43 East Merrick Road in Freeport. He quickly joined in the war effort for both the War Assets Administration and Republic Aircraft in Farmingdale. With the war’s end, a heart condition forced retirement on Soubiran, and he died at the St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens in 1949. He is buried at the Long Island National Cemetery in Farmingdale.

Sources: Soubiran Article, Long Island Daily Press, 01/21/1935. Pg. 7. Decorate 4 of Our Airmen, New York Times, 11/16/1917. Pg. 2. Air Fighter of ’15 ready For War Again. Long Island Daily Press. 09/06/1939. Obituary, Major Robert Soubiran, New York Times, 02/06/1949 pg76

General Sources

Hall, James Norman, ed. The Lafayette Flying Corps. Boston, New York : Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920.

Gordon, Dennis. The Lafayette Flying Corps: The American Volunteers in the French Air Service in World War One. Atglen, PA : Schiffer Publishing, 2000.

Newspapers accessed at www.fultonhistory.com

Thanks to Rocco Cassano, Assistant Director and Kristina Rus, Reference Librarian, East Meadow Public Library.

Frederick Prince was born in Boston, Massachusetts, taking the name of his father Frederick Henry Prince, Sr., a wealthy banker and industrialist. Prince, taught by private tutors in France, also attended the Groton School and Harvard College, while his brother, Norman Prince, became a certified pilot and a founder of the Lafayette Escadrille.

In January 1916, Prince traveled to France, where he joined the Foreign Legion, later taking up aviation alongside his brother in the Escadrille Americaine. A week before Prince started his training, his brother Norman was killed while attempting to land following a combat mission. Prince took up the fight against the Germans and flew with the Escadrille and other units, figuring in twenty-two aerial engagements, for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

After returning to America in 1919, Prince pursued many business enterprises, spending his leisure on fox hunting, polo and yachting. He lived in Marshall, Virginia, and in Old Westbury with his wife, the former Virginia Mitchell. He died at the age of 76 at his home in Old Westbury, ever proud to be part of the great air adventure. His tombstone in the St. John’s Memorial Cemetery in Laurel Hollow bears the symbol of the Lafayette Escadrille.

Sources: Obituary, Frederick H. Prince Jr. Is Dead; Flew With Lafayette Escadrille. New York Times, 10/06/1962. Pg. 25. Various web sites. St. John’s Memorial Cemetery, Laurel Hollow.

Robert Soubiran (1886-1949)

Born in France, young Robert Soubiran immigrated with his parents to America. His first job was as a newspaper boy. At the Simplex Motor Company, he quickly advanced from mechanic to full- time racing car driver, competing in car races. At the outbreak of the Great War, Soubiran became one of the first American volunteers to join the French Foreign Legion.

In the second year of the war, Soubiran was wounded and hospitalized during the Champagne Offensive. After his recovery, he joined the Lafayette Escadrille and completed over 400 missions, flying for French and American aviation. In one action he was surrounded by four German aircraft, saved only by the heroic interference of another Lafayette pilot. His first score was recorded on Oct 17, 1917, though in a newspaper interview twenty years later, he claimed at least six more downed planes—an assertion more likely true than not, as French standards of accountability in matters of military engagement were so high.

While serving as a pilot Soubiran married Ann Marie Choudry and would later have three daughters by this union. Soubiran also became the unofficial photographer of the Escadrille and these historic photographs of their activities were donated to the Smithsonian Institute after his death by his wife. When America entered the war, Soubiran joined the 103rd Pursuit Squadron and rose to be its commanding officer. Before his honorable discharge as a Major, Soubiran was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor by the French government.

After the war, Soubiran served as a sales representative for Delco Manufacturing Company. Later in the 1920s he worked in France for General Motors until the deepening depression eliminated his position. On returning to the United States, he became general manager at one of Frederick Prince’s estates, settling down for the remainder of his life at 138 Kenneth Street in Baldwin.

The outbreak of World War II found Soubiran running his sister’s antique store at 43 East Merrick Road in Freeport. He quickly joined in the war effort for both the War Assets Administration and Republic Aircraft in Farmingdale. With the war’s end, a heart condition forced retirement on Soubiran, and he died at the St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens in 1949. He is buried at the Long Island National Cemetery in Farmingdale.

Sources: Soubiran Article, Long Island Daily Press, 01/21/1935. Pg. 7. Decorate 4 of Our Airmen, New York Times, 11/16/1917. Pg. 2. Air Fighter of ’15 ready For War Again. Long Island Daily Press. 09/06/1939. Obituary, Major Robert Soubiran, New York Times, 02/06/1949 pg76

General Sources

Hall, James Norman, ed. The Lafayette Flying Corps. Boston, New York : Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920.

Gordon, Dennis. The Lafayette Flying Corps: The American Volunteers in the French Air Service in World War One. Atglen, PA : Schiffer Publishing, 2000.

Newspapers accessed at www.fultonhistory.com

Thanks to Rocco Cassano, Assistant Director and Kristina Rus, Reference Librarian, East Meadow Public Library.

The Long Island Flyboys

Part II: The Lafayette Flying Corps

By Robert L. Harrison

The following pilots, assigned to the various French squadrons known as the Lafayette Flying Corps, at some point in their lives had a connection to Long Island. Some may at first have volunteered in the ambulance service or the French Foreign Legion before flying to defend France in World War I. Some came from wealthy families. Three left college to join the war. In total, they may have shot down six enemy aircraft while themselves crashing as many times. They were a brave group. Five lost their lives in combat.

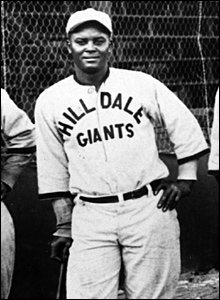

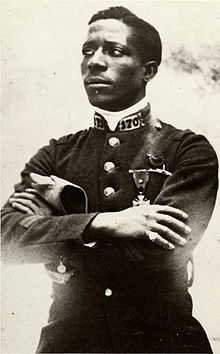

Eugene Jacque Bullard (1895-1961)

Born in Georgia, Bullard was living in France at the beginning of the war. He joined the French Foreign Legion on his nineteenth birthday and served with many flyboys in the Legion, including William Dugan and Robert Soubiran. He joined the Lafayette Flying Corps as the first African American combat pilot. He witnessed the crashing of “Red” Scanlon’s plane into the airfield bakery on his airbase and was photographed with Dennis Dowd from Sea Cliff with other Long Island pilots. James McMillen from Kensington thought highly of him when they trained together.

Bullard flew some 20 missions with the Corps and once crashed near German lines. A German machine gunner had put 78 bullets into his plane, pinning down Bullard until he was rescued. Even so, when America entered the war, Bullard was denied his flying status with the newly formed U.S. Aviation squadrons. The French government, however, awarded Bullard 15 medals for his valor, including the Legion of Honor.

Bullard did not return to New York City until 1940, and found himself needing assistance to bring his daughters home as well from Paris. It was Thomas Hitchcock, Jr., from Old Westbury who helped contribute money for their passage to America. He eventually came to work in Brooklyn after WW II and visited on many occasions his good friend Louis Armstrong in Queens.

Bullard’s life has been portrayed in books, plays, articles and movies. Ernest Hemingway may have modeled the Zelli’s Jazz Club drummer after Bullard in The Sun Also Rises. The 2007 movie Flyboys portrayed Bullard as the character Skinner. He died of stomach cancer at 67 and is buried in the French Veterans Cemetery in Flushing.

Sources: “Eugene Bullard, Ex-Pilot, Dead.” Obituary, The New York Times, 10/14/1961. Pg23. Lloyd, Craig. Eugene Bullard Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris, University of Georgia Press, 2000. George Vecsey & George Dade, Getting Off The Ground, E. P. Dutton, 1979.

Russell Bracken Corey (1894-1954)

Corey, born in New York City, attended New York public schools and, for a time, studied in France, before graduating from Yale University’s Sheffield Scientific School. In the summer of 1917, he journeyed to France to train as a pilot in the Lafayette Flying Corps. In one mission he was injured in an airplane accident over German lines. Some accounts of his service credit him with one downed aircraft, but this was never confirmed. When America entered the war, Corey joined the U.S. Navel Flying Corps and was on active duty until he received his honorable discharge as a lieutenant in 1919.

Returning to civilian life, Corey became involved with the real estate and insurance businesses in New York City and Long Island. In 1924, Corey married Miss Margaret Caffrey at Church of St. Mary Star-of-the Sea in Far Rockaway. When World War II started, he rejoined the Navy and served in various capacities before his discharge with the rank of Commander, receiving the Bronze Star among other medals.

After the war Corey commuted to his business interests in the city from his home in Kensington. He was well known in yachting circles as a member of the Manhasset Bay Yacht Club. Corey died at the age of 59 at his home on 42 Beverly Road in Kensington. He was buried at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Mt. Pleasant, NY.

Sources: 1910 U.S. Federal Census. “Brooklynites at Yale,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 10/08/1918. “Miss Caffey A Bride,” The New York Times, 02/14/1924, pg 24. Obituary, Newsday, 05/05/1954, pg125. “Russell B. Corey, Real Estate Man,” Obituary, The New York Times, 05/04/1954, pg 29.

Dennis P. Dowd, Jr. (1887-1916)

Dowd was born in New York City to a wealthy family, his father having earned great success in the city’s real estate markets. He grew up in Sea Cliff and graduated from Georgetown University in 1908. Afterwards, he pursued his law degree at Columbia University, later practicing in Brooklyn and Alabama.

When his fiancée proved unwilling to commit to a marriage date, Dowd sailed for France in August 1914. In Late that month he became one of the first volunteers from America to join the French Foreign Legion. In the 1915 battle of Champagne, Dowd was wounded badly from a shell explosion. With his right hand crippled, he taught himself to write with his left hand. While in the hospital, Dowd fell in love with Paulette Parent de Saint-Glyn, a French debutante. They planned to be married as soon as Dowd completed his training as a pilot in French Aviation.

Although Dowd volunteered as a pilot flyer after his release from the hospital, his physician marked his release with the wrong stamp, sending him to an insane asylum. It took him several days to convince the authorities that he was indeed sane and eligible to pursue his service as a fighter pilot in the defense of France. On August 12, 1916, during one of his final training flights, Dowd’s plane went into a free fall at around three hundred feet and crashed, killing him instantly. The news of his death spread quickly back to America and the Sea Cliff community. He was the second American airman to be killed in France and the first to die in training. By his request Dowd was laid to rest in France in the St. Germaine Cemetery, before final burial at the Escadrille Lafayette Memorial near Paris. Three years later his former bride-to-be, now married, came to America to visit the Dowds in Sea Cliff.

Dowd is not forgotten. A tree planted in his name stands in Clifton Park near his family’s home on Locust Street, and his name appears on a plaque commemorating Sea Cliff’s war dead the war.

Sources: “New Yorker To Wed His War ‘Godmother.’” The New York Times, 03/15/1916. “Sea Cliff Mourns Death of Aviator,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 08/14/1916. “France Honors Memory of Dowd”, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 03/06/1918. “War Bride Visits Sea Cliff Family,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 08/14/1919. “Anniversary of Hero’s Death,” Sea Cliff News, 08/11/1934. Sea Cliff Museum.

Fearchar I. Ferguson (1896-1972)

Ferguson was born in New York City to Farquhar and Juliana Armour Ferguson. He and his six siblings were raised in the city and in Huntington Bay. His family’s huge estate on Shore Road in Halsite was later known as Ferguson’s Castle. Ferguson’s mother, heiress to the Armour meat packing fortune, figured prominently in North Shore social life.

Ferguson left for Europe in May 1917 to join the Lafayette Flying Corps, becoming one of the youngest Americans to fly for France. After his aero training, he was assigned to Spad 96, a squadron which ultimately lost very many of its fighter pilots. In one aero battle, Ferguson was attacked by eight German Albatross planes, escaping some 45 minutes later with 28 bullet holes in his plane. He often flew alone over the enemy lines, returning at dusk with only the sound of his motor to alert his field mechanics. In one account he was credited with shooting an enemy plane down, but since there were no witnesses to his lone flights, there might have been even more. Ferguson was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm by the French Government for his service in the war.

His brother Danforth also served, first as an ambulance driver, and then in the 42nd United States Coast Guard Artillery. Danforth would die in France of influenza in 1918. Both brothers appear on the World War I memorial plaque in Huntington Town Hall.

After the War, Ferguson married Miss Ruth Amory from Troy, New York, and lived in Greenwich, Connecticut. They moved later to Easton, Maryland, where he died of cancer in 1972. His burial was at the Amour Mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York.

Sources: “Ferguson Married, Ruth Amory of Troy,” The New York Times, 05/10/1925. “Came here with Croix de Guerre with Palm,” New York Herald, 03/14/1919. Fultonhistory.com. “Obituary: Danforth Brooks Ferguson,” The Long Islander, 11/29/1918. “Obituary: Fearchar I Ferguson,” New York Times, 02/01/1972, P40.

Eric Anderson Fowler (1895-1917)

Although Fowler was born in Quogue, Long Island, he spent his youth in Manhattan. The son of wealthy businessman Anderson Fowler and mother Emily Arthur Fowler, he attended private schools in New York and Pennsylvania, before entering Princeton University, withdrawing in August 1916 to join the war in Europe.

He first joined the American Ambulance Service that summer, and in 1917 volunteered for the French Aviation Service. Fowler’s training went smoothly and after promotion to corporal he started his acrobatic training. On his graduation day Fowler was flying with forty other planes when his plane suddenly dived to the ground, killing him instantly.

It was thought later that he had somehow lost consciousness, since everything about the plane’s mechanical condition seemed satisfactory. His remains were laid to rest in the Lafayette Memorial near Paris.

In 1919, his mother received a “War Diploma” from Princeton University as a tribute to Eric’s war service as a Princeton student. The Fowler family had at least five other children involved in the war, either in the ambulance services, U.S. Army, and aviation branches. Eric’s brother Harold, who lived in Southampton most of his life, was an aviator both for England and America during the war.

Sources: 1900 Federal Census, 1910 Federal Census. Obituary, The New York Times, 12/02/17, E5. Saitonstall, Nora. Out Here in the Front, WW Letters, Northeastern University Press, 2004.

James Grier (1896-1920)

Grier was born in Philadelphia and later attended Temple College briefly before joining the American Ambulance Service in France. While in Paris, Grier changed his mind and enlisted instead in the French Aviation Service, for which he was accredited as a pilot in January 1918. That spring Grier enrolled in the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps as an ensign. After the armistice, he returned to America and served briefly on the USS Oklahoma and Arizona. After tours of duty at Langley Field and at the Bay Shore Sea Station, Grier was transferred to Mitchell Field in Garden City.

On September 5, 1920, Lieutenant Grier was assigned with Sgt. Joseph Saxe to take aerial photographs of the National tennis matches at nearby Forest Hills. Taking off in the afternoon on a JN-Curtiss plane, they arrived within minutes to view a match between William “Big Bill” Tilden and Wallace Johnson. The stadium was packed with more than 10,000 fans, who became annoyed when Grier steered his plane just 200 feet above them. After a few more passes the Curtis conked out, and black smoke came pouring out of the engine. To the fans’ horror, the plane crashed nose first just outside the stadium. Sgt. Saxe was declared dead at the scene, though Grier survived until the next morning at St. John’s Hospital in Long Island City before he too was succumbed to his injuries. Grier was buried in his native Philadelphia.

Sources: “10,000 See Plane Kill Two in Crash,” The New York Times, 09/17/1920. Fultonhistory.com.

Thomas Hitchcock, Jr (1900-1944)

As son of Louise and Thomas Hitchcock, “Tommy” Hitchcock was born into a wealthy sporting family. Born in Aiken, South Carolina, he spent a great deal of his life on Long Island’s North Shore as well. His father, a renowned horse trainer and polo player, was a founder of the Meadow Brook Club. Young Hitchcock followed his father’s love for polo, competing in his first tournament at 13. In 1916 Hitchcock was part of the polo team that won the U.S. National Junior Championship.

Hitchcock attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire, where he excelled in sports. When the war in Europe started, he withdrew from school to join the French Aviation Service to become one of the youngest pilots serving in the Lafayette Flying Corps. He crashed shortly after shooting down his first plane but survived unhurt. In another battle he came flying down on two German planes at once, only to discover a third enemy plane overhead. Hitchcock crashed. Taken prisoner, he spent two months in a German hospital before transfer to a prison camp. Enroute by train, Hitchcock stole a map from his guard and jumped from the railcar. He avoided capture for eight days making his way to Switzerland, traveling at night for some one hundred miles. The American press covered his capture and escape, transforming him into one of the war’s early American heroes. The French awarded Hitchcock the Croix de Guerre with three palms. Released from French service with the rank of lieutenant, he returned home in 1918.

Hitchcock’s began his port-war life by enrolling at both Harvard and, for a time, at Oxford University in England. Upon his Harvard graduation, Hitchcock resumed his polo career to become a world-famous rider, rated a ten-goal player in almost every year he participated. In 1924 Hitchcock won a silver medal as part of the U.S. Olympic Polo Team, at a time when Long Island had become the leading center for the sport.

In 1928, Hitchcock married Margaret Mellon. Together, they raised four children, while living in Sands Point and on Broad Hollow Farm in Old Westbury. Having joined Lehman Brothers during the 1930s, he began piloting his own Fairchild 24 to Manhattan from Sands Point.

On retiring from polo, Hitchcock sold his stable of horses and tried to return to active military service as an Army fighter pilot in World War II. It was decided, however, that he could better serve, at age 41, as an air attaché in England, where he oversaw the development of the P-51 mustang fighter, which had hitherto experienced many problems. The plane’s troubles continued and eventually cost Hitchcock his life in a test-flight crash. He was buried with honors at the Cambridge American Cemetery in England.

Hitchcock’s legacy lives in books and films. His friend F Scott Fitzgerald may possibly have made some use of Hitchcock as a model for Tom Buchanan (The Great Gatsby) and Tommy Barban (Tender is the Night). Nelson W. Aldrich subtitled his biography of Hitchcock An American Hero, while his character appeared in the 1958 film Lafayette Escadrille. In 1990 Hitchcock was inducted posthumously into the Museum of Polo and the Polo Hall of Fame. The family name today lends itself to Hitchcock Lane on Broad Hollow Farm in Old Westbury.

Sources: Frost, Donald, “10 Goal Pilot,” Popular Aviation, July 1939. “Tommy Hitchcock Dies in Crash,” Newsday, 04/20/1944, pg3. 1910 United States Federal Census. 1925 New York State Census. “No News of Hitchcock,” Long Island Farmer, April 1917.

Dabney Horton (1891-1968)

Horton was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1915. During his active youth he became an expect skier. Early in the war he volunteered for the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Service, where he was assigned to transport the wounded French soldiers back from the front. A year later, Horton joined the French Aviation Service, flying missions as fighter pilot, photo reconnaissance to bomber, and scout. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre medal with star.

Horton married Helen Wheelock Hubbard in Paris on January 7, 1917. Returning then to civilian life in the States, he held a variety of jobs, as sports writer, aviation poet, and English instructor at Ohio State University. During his teaching tenure, local police raided his home and uncovered an illegal whiskey still. His teaching position was terminated.

Before the Second World War, Horton settled on Long Island in Northport and gained fulltime employment at Republic Aviation in Farmingdale, working as a machinist until retiring in 1957. Eleven years later Dabney Horton passed away in Huntington Hospital.

Sources: 1940 Federal Census (occupation Stone Writer). “University Instructor Seized in Moonshine Raid”, The New York Times, 12/10/1925.

James Haitt McMillen (c. 1891-1979)

McMillen was born in Ohio and moved with his family to Chicago and then to New York City to pursue a career on Wall Street (his father was a prosperous banker). He did attend college but never earned his degree. In early 1917, McMillen read about the war in Europe and believed that France was right and needed help. He took a train to Virginia with Tommy Hitchcock from Old Westbury, passed his initial examination for flight training, and arrived in France in February. Receiving his wings on June, he was assigned to Spad 38 of the Lafayette Flying Corps, where he became involved in heavy aero fighting during the summer and fall before attaining the rank of sergeant. The government of France later awarded him the Croix de Guerre medal for his service. When America entered the war, he joined his country’s air service, which promoted him to first lieutenant. He flew again for Spad 38 until September 28, 1918.

On arriving back in the States, McMillen married Miss Alberta Weber and settled down, first in Montclair, New Jersey, and later New York City. Alberta, who had previously won the women’s New Jersey State tennis championship, was an avid golfer as well, and became a founding member of the Women’s Long Island Golf Association after moving with McMillen to Kensington, Long Island, in 1930.

The McMillens raised their two children at 58 Beverly Road in Kensington, not far from where Lafayette flyer Russell Corey lived. He followed a career in investment brokerage for the firm of Stillman, Maynard & Company. After his wife passed away in 1964, McMillen rented a room at the Creek Club in Lattingtown, where he was interviewed shortly before his death for the book Getting Off the Ground. When asked what his greatest fear was during his flight service, he replied, “Walking to my plane. Once you got off the ground you were fine.”

Sources: Vecsey, George & Dade, George C. Getting Off the Ground, E.F. Dutton, 1979. 1930-1940 U.S. Federal Census. “Mrs. James McMillen, Obituary,” The New York Times, May 4th 1964. Cradle of Aviation Museum display, Garden City, NY.

Lawrence “Red” Scanlon (1893-1920)

Scanlon was born in Cedarhurst and attended local schools until enrolling at Seton Hall College in 1914. He studied electrical engineering up until the time he ran off to Europe with his friend Russell A. Kelly to fight for France in the Great War. They worked their way over to England on a cattle boat and soon joined the French Foreign Legion. In the summer of 1915, Scanlon and Kelly were both fighting at Souches when the Germans overran their position and captured Kelly (who later died). Scanlon was wounded both in the thigh and in the ankle by machine gun fire and was not found by the ambulance corps until some 56 hours later. Because of his heroic defense of France, Scanlon was awarded the Croix de Guerre. He was the first American volunteer to be honored with this medal.

After being hospitalized for over a year, Scanlon was invalided out of the Legion. This did not stop him, however, from joining up with the French aviation service (Lafayette Flying Corps) and fighting for France and liberty again. His operations had left one leg some six inches shorter than the other, a condition which made flying difficult. Scanlon, in training, suffered some crashes, most memorably crashing into the airfield bakery. He climbed down from the roof unhurt while his fellow airmen were still looking for the dead pilot. After he admitted that he indeed was the pilot, his fellow volunteers rejoiced in his good luck.

His leg injuries forced him to give up for good his dream of flying for France. Returning to America in 1917, Scanlon worked briefly as an electrical contractor until his old wounds required still more operations. He entered a New York hospital, where he died on November 25, 1920. Thirty-eight years later he was portrayed in the movie Lafayette Escadrille by the actor Denny Devine.

Sources: “Cedarhurst Boys Coming From War; One Badly Injured.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10/15/1915. “Was Behind the Lines Before Being Found,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 06/25/1917. 1920 Federal Census: The Scanlon family lived on Cedarhurst Avenue. 1915 New York State Census: Listed as Laurence Scanlon.

Part II: The Lafayette Flying Corps

By Robert L. Harrison

The following pilots, assigned to the various French squadrons known as the Lafayette Flying Corps, at some point in their lives had a connection to Long Island. Some may at first have volunteered in the ambulance service or the French Foreign Legion before flying to defend France in World War I. Some came from wealthy families. Three left college to join the war. In total, they may have shot down six enemy aircraft while themselves crashing as many times. They were a brave group. Five lost their lives in combat.

Eugene Jacque Bullard (1895-1961)

Born in Georgia, Bullard was living in France at the beginning of the war. He joined the French Foreign Legion on his nineteenth birthday and served with many flyboys in the Legion, including William Dugan and Robert Soubiran. He joined the Lafayette Flying Corps as the first African American combat pilot. He witnessed the crashing of “Red” Scanlon’s plane into the airfield bakery on his airbase and was photographed with Dennis Dowd from Sea Cliff with other Long Island pilots. James McMillen from Kensington thought highly of him when they trained together.

Bullard flew some 20 missions with the Corps and once crashed near German lines. A German machine gunner had put 78 bullets into his plane, pinning down Bullard until he was rescued. Even so, when America entered the war, Bullard was denied his flying status with the newly formed U.S. Aviation squadrons. The French government, however, awarded Bullard 15 medals for his valor, including the Legion of Honor.

Bullard did not return to New York City until 1940, and found himself needing assistance to bring his daughters home as well from Paris. It was Thomas Hitchcock, Jr., from Old Westbury who helped contribute money for their passage to America. He eventually came to work in Brooklyn after WW II and visited on many occasions his good friend Louis Armstrong in Queens.

Bullard’s life has been portrayed in books, plays, articles and movies. Ernest Hemingway may have modeled the Zelli’s Jazz Club drummer after Bullard in The Sun Also Rises. The 2007 movie Flyboys portrayed Bullard as the character Skinner. He died of stomach cancer at 67 and is buried in the French Veterans Cemetery in Flushing.

Sources: “Eugene Bullard, Ex-Pilot, Dead.” Obituary, The New York Times, 10/14/1961. Pg23. Lloyd, Craig. Eugene Bullard Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris, University of Georgia Press, 2000. George Vecsey & George Dade, Getting Off The Ground, E. P. Dutton, 1979.

Russell Bracken Corey (1894-1954)

Corey, born in New York City, attended New York public schools and, for a time, studied in France, before graduating from Yale University’s Sheffield Scientific School. In the summer of 1917, he journeyed to France to train as a pilot in the Lafayette Flying Corps. In one mission he was injured in an airplane accident over German lines. Some accounts of his service credit him with one downed aircraft, but this was never confirmed. When America entered the war, Corey joined the U.S. Navel Flying Corps and was on active duty until he received his honorable discharge as a lieutenant in 1919.

Returning to civilian life, Corey became involved with the real estate and insurance businesses in New York City and Long Island. In 1924, Corey married Miss Margaret Caffrey at Church of St. Mary Star-of-the Sea in Far Rockaway. When World War II started, he rejoined the Navy and served in various capacities before his discharge with the rank of Commander, receiving the Bronze Star among other medals.

After the war Corey commuted to his business interests in the city from his home in Kensington. He was well known in yachting circles as a member of the Manhasset Bay Yacht Club. Corey died at the age of 59 at his home on 42 Beverly Road in Kensington. He was buried at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Mt. Pleasant, NY.

Sources: 1910 U.S. Federal Census. “Brooklynites at Yale,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 10/08/1918. “Miss Caffey A Bride,” The New York Times, 02/14/1924, pg 24. Obituary, Newsday, 05/05/1954, pg125. “Russell B. Corey, Real Estate Man,” Obituary, The New York Times, 05/04/1954, pg 29.

Dennis P. Dowd, Jr. (1887-1916)

Dowd was born in New York City to a wealthy family, his father having earned great success in the city’s real estate markets. He grew up in Sea Cliff and graduated from Georgetown University in 1908. Afterwards, he pursued his law degree at Columbia University, later practicing in Brooklyn and Alabama.

When his fiancée proved unwilling to commit to a marriage date, Dowd sailed for France in August 1914. In Late that month he became one of the first volunteers from America to join the French Foreign Legion. In the 1915 battle of Champagne, Dowd was wounded badly from a shell explosion. With his right hand crippled, he taught himself to write with his left hand. While in the hospital, Dowd fell in love with Paulette Parent de Saint-Glyn, a French debutante. They planned to be married as soon as Dowd completed his training as a pilot in French Aviation.

Although Dowd volunteered as a pilot flyer after his release from the hospital, his physician marked his release with the wrong stamp, sending him to an insane asylum. It took him several days to convince the authorities that he was indeed sane and eligible to pursue his service as a fighter pilot in the defense of France. On August 12, 1916, during one of his final training flights, Dowd’s plane went into a free fall at around three hundred feet and crashed, killing him instantly. The news of his death spread quickly back to America and the Sea Cliff community. He was the second American airman to be killed in France and the first to die in training. By his request Dowd was laid to rest in France in the St. Germaine Cemetery, before final burial at the Escadrille Lafayette Memorial near Paris. Three years later his former bride-to-be, now married, came to America to visit the Dowds in Sea Cliff.

Dowd is not forgotten. A tree planted in his name stands in Clifton Park near his family’s home on Locust Street, and his name appears on a plaque commemorating Sea Cliff’s war dead the war.

Sources: “New Yorker To Wed His War ‘Godmother.’” The New York Times, 03/15/1916. “Sea Cliff Mourns Death of Aviator,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 08/14/1916. “France Honors Memory of Dowd”, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 03/06/1918. “War Bride Visits Sea Cliff Family,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 08/14/1919. “Anniversary of Hero’s Death,” Sea Cliff News, 08/11/1934. Sea Cliff Museum.

Fearchar I. Ferguson (1896-1972)

Ferguson was born in New York City to Farquhar and Juliana Armour Ferguson. He and his six siblings were raised in the city and in Huntington Bay. His family’s huge estate on Shore Road in Halsite was later known as Ferguson’s Castle. Ferguson’s mother, heiress to the Armour meat packing fortune, figured prominently in North Shore social life.

Ferguson left for Europe in May 1917 to join the Lafayette Flying Corps, becoming one of the youngest Americans to fly for France. After his aero training, he was assigned to Spad 96, a squadron which ultimately lost very many of its fighter pilots. In one aero battle, Ferguson was attacked by eight German Albatross planes, escaping some 45 minutes later with 28 bullet holes in his plane. He often flew alone over the enemy lines, returning at dusk with only the sound of his motor to alert his field mechanics. In one account he was credited with shooting an enemy plane down, but since there were no witnesses to his lone flights, there might have been even more. Ferguson was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm by the French Government for his service in the war.

His brother Danforth also served, first as an ambulance driver, and then in the 42nd United States Coast Guard Artillery. Danforth would die in France of influenza in 1918. Both brothers appear on the World War I memorial plaque in Huntington Town Hall.

After the War, Ferguson married Miss Ruth Amory from Troy, New York, and lived in Greenwich, Connecticut. They moved later to Easton, Maryland, where he died of cancer in 1972. His burial was at the Amour Mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York.

Sources: “Ferguson Married, Ruth Amory of Troy,” The New York Times, 05/10/1925. “Came here with Croix de Guerre with Palm,” New York Herald, 03/14/1919. Fultonhistory.com. “Obituary: Danforth Brooks Ferguson,” The Long Islander, 11/29/1918. “Obituary: Fearchar I Ferguson,” New York Times, 02/01/1972, P40.

Eric Anderson Fowler (1895-1917)

Although Fowler was born in Quogue, Long Island, he spent his youth in Manhattan. The son of wealthy businessman Anderson Fowler and mother Emily Arthur Fowler, he attended private schools in New York and Pennsylvania, before entering Princeton University, withdrawing in August 1916 to join the war in Europe.

He first joined the American Ambulance Service that summer, and in 1917 volunteered for the French Aviation Service. Fowler’s training went smoothly and after promotion to corporal he started his acrobatic training. On his graduation day Fowler was flying with forty other planes when his plane suddenly dived to the ground, killing him instantly.

It was thought later that he had somehow lost consciousness, since everything about the plane’s mechanical condition seemed satisfactory. His remains were laid to rest in the Lafayette Memorial near Paris.

In 1919, his mother received a “War Diploma” from Princeton University as a tribute to Eric’s war service as a Princeton student. The Fowler family had at least five other children involved in the war, either in the ambulance services, U.S. Army, and aviation branches. Eric’s brother Harold, who lived in Southampton most of his life, was an aviator both for England and America during the war.

Sources: 1900 Federal Census, 1910 Federal Census. Obituary, The New York Times, 12/02/17, E5. Saitonstall, Nora. Out Here in the Front, WW Letters, Northeastern University Press, 2004.

James Grier (1896-1920)

Grier was born in Philadelphia and later attended Temple College briefly before joining the American Ambulance Service in France. While in Paris, Grier changed his mind and enlisted instead in the French Aviation Service, for which he was accredited as a pilot in January 1918. That spring Grier enrolled in the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps as an ensign. After the armistice, he returned to America and served briefly on the USS Oklahoma and Arizona. After tours of duty at Langley Field and at the Bay Shore Sea Station, Grier was transferred to Mitchell Field in Garden City.

On September 5, 1920, Lieutenant Grier was assigned with Sgt. Joseph Saxe to take aerial photographs of the National tennis matches at nearby Forest Hills. Taking off in the afternoon on a JN-Curtiss plane, they arrived within minutes to view a match between William “Big Bill” Tilden and Wallace Johnson. The stadium was packed with more than 10,000 fans, who became annoyed when Grier steered his plane just 200 feet above them. After a few more passes the Curtis conked out, and black smoke came pouring out of the engine. To the fans’ horror, the plane crashed nose first just outside the stadium. Sgt. Saxe was declared dead at the scene, though Grier survived until the next morning at St. John’s Hospital in Long Island City before he too was succumbed to his injuries. Grier was buried in his native Philadelphia.

Sources: “10,000 See Plane Kill Two in Crash,” The New York Times, 09/17/1920. Fultonhistory.com.

Thomas Hitchcock, Jr (1900-1944)

As son of Louise and Thomas Hitchcock, “Tommy” Hitchcock was born into a wealthy sporting family. Born in Aiken, South Carolina, he spent a great deal of his life on Long Island’s North Shore as well. His father, a renowned horse trainer and polo player, was a founder of the Meadow Brook Club. Young Hitchcock followed his father’s love for polo, competing in his first tournament at 13. In 1916 Hitchcock was part of the polo team that won the U.S. National Junior Championship.

Hitchcock attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire, where he excelled in sports. When the war in Europe started, he withdrew from school to join the French Aviation Service to become one of the youngest pilots serving in the Lafayette Flying Corps. He crashed shortly after shooting down his first plane but survived unhurt. In another battle he came flying down on two German planes at once, only to discover a third enemy plane overhead. Hitchcock crashed. Taken prisoner, he spent two months in a German hospital before transfer to a prison camp. Enroute by train, Hitchcock stole a map from his guard and jumped from the railcar. He avoided capture for eight days making his way to Switzerland, traveling at night for some one hundred miles. The American press covered his capture and escape, transforming him into one of the war’s early American heroes. The French awarded Hitchcock the Croix de Guerre with three palms. Released from French service with the rank of lieutenant, he returned home in 1918.

Hitchcock’s began his port-war life by enrolling at both Harvard and, for a time, at Oxford University in England. Upon his Harvard graduation, Hitchcock resumed his polo career to become a world-famous rider, rated a ten-goal player in almost every year he participated. In 1924 Hitchcock won a silver medal as part of the U.S. Olympic Polo Team, at a time when Long Island had become the leading center for the sport.

In 1928, Hitchcock married Margaret Mellon. Together, they raised four children, while living in Sands Point and on Broad Hollow Farm in Old Westbury. Having joined Lehman Brothers during the 1930s, he began piloting his own Fairchild 24 to Manhattan from Sands Point.

On retiring from polo, Hitchcock sold his stable of horses and tried to return to active military service as an Army fighter pilot in World War II. It was decided, however, that he could better serve, at age 41, as an air attaché in England, where he oversaw the development of the P-51 mustang fighter, which had hitherto experienced many problems. The plane’s troubles continued and eventually cost Hitchcock his life in a test-flight crash. He was buried with honors at the Cambridge American Cemetery in England.

Hitchcock’s legacy lives in books and films. His friend F Scott Fitzgerald may possibly have made some use of Hitchcock as a model for Tom Buchanan (The Great Gatsby) and Tommy Barban (Tender is the Night). Nelson W. Aldrich subtitled his biography of Hitchcock An American Hero, while his character appeared in the 1958 film Lafayette Escadrille. In 1990 Hitchcock was inducted posthumously into the Museum of Polo and the Polo Hall of Fame. The family name today lends itself to Hitchcock Lane on Broad Hollow Farm in Old Westbury.

Sources: Frost, Donald, “10 Goal Pilot,” Popular Aviation, July 1939. “Tommy Hitchcock Dies in Crash,” Newsday, 04/20/1944, pg3. 1910 United States Federal Census. 1925 New York State Census. “No News of Hitchcock,” Long Island Farmer, April 1917.

Dabney Horton (1891-1968)

Horton was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1915. During his active youth he became an expect skier. Early in the war he volunteered for the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Service, where he was assigned to transport the wounded French soldiers back from the front. A year later, Horton joined the French Aviation Service, flying missions as fighter pilot, photo reconnaissance to bomber, and scout. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre medal with star.

Horton married Helen Wheelock Hubbard in Paris on January 7, 1917. Returning then to civilian life in the States, he held a variety of jobs, as sports writer, aviation poet, and English instructor at Ohio State University. During his teaching tenure, local police raided his home and uncovered an illegal whiskey still. His teaching position was terminated.

Before the Second World War, Horton settled on Long Island in Northport and gained fulltime employment at Republic Aviation in Farmingdale, working as a machinist until retiring in 1957. Eleven years later Dabney Horton passed away in Huntington Hospital.

Sources: 1940 Federal Census (occupation Stone Writer). “University Instructor Seized in Moonshine Raid”, The New York Times, 12/10/1925.

James Haitt McMillen (c. 1891-1979)

McMillen was born in Ohio and moved with his family to Chicago and then to New York City to pursue a career on Wall Street (his father was a prosperous banker). He did attend college but never earned his degree. In early 1917, McMillen read about the war in Europe and believed that France was right and needed help. He took a train to Virginia with Tommy Hitchcock from Old Westbury, passed his initial examination for flight training, and arrived in France in February. Receiving his wings on June, he was assigned to Spad 38 of the Lafayette Flying Corps, where he became involved in heavy aero fighting during the summer and fall before attaining the rank of sergeant. The government of France later awarded him the Croix de Guerre medal for his service. When America entered the war, he joined his country’s air service, which promoted him to first lieutenant. He flew again for Spad 38 until September 28, 1918.

On arriving back in the States, McMillen married Miss Alberta Weber and settled down, first in Montclair, New Jersey, and later New York City. Alberta, who had previously won the women’s New Jersey State tennis championship, was an avid golfer as well, and became a founding member of the Women’s Long Island Golf Association after moving with McMillen to Kensington, Long Island, in 1930.

The McMillens raised their two children at 58 Beverly Road in Kensington, not far from where Lafayette flyer Russell Corey lived. He followed a career in investment brokerage for the firm of Stillman, Maynard & Company. After his wife passed away in 1964, McMillen rented a room at the Creek Club in Lattingtown, where he was interviewed shortly before his death for the book Getting Off the Ground. When asked what his greatest fear was during his flight service, he replied, “Walking to my plane. Once you got off the ground you were fine.”

Sources: Vecsey, George & Dade, George C. Getting Off the Ground, E.F. Dutton, 1979. 1930-1940 U.S. Federal Census. “Mrs. James McMillen, Obituary,” The New York Times, May 4th 1964. Cradle of Aviation Museum display, Garden City, NY.

Lawrence “Red” Scanlon (1893-1920)

Scanlon was born in Cedarhurst and attended local schools until enrolling at Seton Hall College in 1914. He studied electrical engineering up until the time he ran off to Europe with his friend Russell A. Kelly to fight for France in the Great War. They worked their way over to England on a cattle boat and soon joined the French Foreign Legion. In the summer of 1915, Scanlon and Kelly were both fighting at Souches when the Germans overran their position and captured Kelly (who later died). Scanlon was wounded both in the thigh and in the ankle by machine gun fire and was not found by the ambulance corps until some 56 hours later. Because of his heroic defense of France, Scanlon was awarded the Croix de Guerre. He was the first American volunteer to be honored with this medal.

After being hospitalized for over a year, Scanlon was invalided out of the Legion. This did not stop him, however, from joining up with the French aviation service (Lafayette Flying Corps) and fighting for France and liberty again. His operations had left one leg some six inches shorter than the other, a condition which made flying difficult. Scanlon, in training, suffered some crashes, most memorably crashing into the airfield bakery. He climbed down from the roof unhurt while his fellow airmen were still looking for the dead pilot. After he admitted that he indeed was the pilot, his fellow volunteers rejoiced in his good luck.

His leg injuries forced him to give up for good his dream of flying for France. Returning to America in 1917, Scanlon worked briefly as an electrical contractor until his old wounds required still more operations. He entered a New York hospital, where he died on November 25, 1920. Thirty-eight years later he was portrayed in the movie Lafayette Escadrille by the actor Denny Devine.

Sources: “Cedarhurst Boys Coming From War; One Badly Injured.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10/15/1915. “Was Behind the Lines Before Being Found,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 06/25/1917. 1920 Federal Census: The Scanlon family lived on Cedarhurst Avenue. 1915 New York State Census: Listed as Laurence Scanlon.

|

Clarence Shoninger (1892-1956)

Shoninger was born in Chicago and attended the New York Military Academy. He graduated from Yale University in 1915. After working briefly at B. Altman & Company, he sailed to France and joined the ambulance services in the Great War. Shoninger was assigned to help out in the battle for Verdun and safely evacuated hundreds of the French wounded from the front. Afterwards he joined the French aviation service and proved to be a brave flyer. While on patrol on May 29, 1918, he was attacked by several German albatross airplanes. He maneuvered his aircraft away over several miles until finally he crashed into a German antiaircraft battery. A wounded Shoninger was taken prisoner and sent to a hospital to finish the war in a German prisoner-of-war camp. When released on November 29, 1918, he made his own way back to Paris. The American press wrote about his mistreatment by his German captors. For his service to France, Shoninger was awarded the Croix de Guerre. After returning to America, he married Ruth Dorn of Flushing in 1920. Shoninger settled down in Douglaston, Queens (22 Douglaston Parkway), and held a number of banking jobs while freelancing for aviation magazines. He appeared in |

the1940 United States Census as a welfare investigator. Alcohol abuse, perhaps caused by his war experiences, led at one point to the suspension of his driver’s license.

In the Second World War, Shoninger served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, assisting pilots on prisoner-of-war interrogations. Discharged as a major, he retired to Coral Gables, Florida. In 1956, Shoninger died of a heart attack and was buried in the National Cemetery in Farmingdale, N.Y. (Sec C, 181AA).

Sources: “16 Motorists Loses Licenses,” Long Island Daily Press, 08/16/1935. 1940 Federal Census. “Civil Service Exams,” Long Island Sunday Press, 03/19/1933. “Sgt Clarence Shoninger,” The Post, Ellicottville, NY. 06/25/1919. Fulton History.com.

In the Second World War, Shoninger served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, assisting pilots on prisoner-of-war interrogations. Discharged as a major, he retired to Coral Gables, Florida. In 1956, Shoninger died of a heart attack and was buried in the National Cemetery in Farmingdale, N.Y. (Sec C, 181AA).

Sources: “16 Motorists Loses Licenses,” Long Island Daily Press, 08/16/1935. 1940 Federal Census. “Civil Service Exams,” Long Island Sunday Press, 03/19/1933. “Sgt Clarence Shoninger,” The Post, Ellicottville, NY. 06/25/1919. Fulton History.com.

|

William Tailer (1895-1918)

Tailer was born in Manhattan and raised in Roslyn by his parents Henry and Clara Wright Tailer. His father was president of the Banker’s Trust Company of New York City. As a youth, Tailer was well known as a North Shore sportsman, participating in tennis, golfing and horsemanship. At first employed in his father’s firm, he joined the New York State National Guard in 1916 and was assigned to the Texas-Mexico border. After returning from his military service, Tailer took up flying at the aviation field in Mineola. After earning his flying license, Tailer became impatient waiting to enter the Army Air Corps. With the help of August Belmont, young Tailer was granted permission to serve in the Lafayette Flying Corps in France. |

His aero training in France lasted some five months before he was assigned to the famous Cigognes unit known as The Storks. Tailer flew at the front during the winter of 1918 until he was shot down by German antiaircraft fire near Verdun. He was the first American volunteer from Roslyn to be killed in the Great War. In his memory a requiem mass was said for him at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. The Long Island community also raised money for a bronze tablet to be installed in his honor near the Roslyn Clock Tower. His body was later interred at the Lafayette Memorial near Paris, France.

Sources: “W.H. Tailer A Fine Flier,” The New York Times, 02/09/1918. “American Aviator Killed,” The Oregonian, 02/08/1918. “Memorial To Dead Roslyn Aviator,” Hempstead Sentinel, 04/04/18. “Solemn Requiem Mass,” N.Y. Herald, 03/08/1918. 1900 United States Federal Census.

These are the stories of those Lafayette pilots of Long Island. New York City, including Kings and Queens counties, had their share as well of brave men who flew to the defense of France before the United States entered the war.

For further reading about the Lafayette Escadrille and Flying Corps, Nordhoff and Hall’s two volume book, The Lafayette Flying Corps provides a biographical sketch of each volunteer. A more recent book, with new information on these lives, is Dennis Gordon’s, The Lafayette Flying Corps: The American Volunteers in the French Air Service.

Sources: “W.H. Tailer A Fine Flier,” The New York Times, 02/09/1918. “American Aviator Killed,” The Oregonian, 02/08/1918. “Memorial To Dead Roslyn Aviator,” Hempstead Sentinel, 04/04/18. “Solemn Requiem Mass,” N.Y. Herald, 03/08/1918. 1900 United States Federal Census.

These are the stories of those Lafayette pilots of Long Island. New York City, including Kings and Queens counties, had their share as well of brave men who flew to the defense of France before the United States entered the war.

For further reading about the Lafayette Escadrille and Flying Corps, Nordhoff and Hall’s two volume book, The Lafayette Flying Corps provides a biographical sketch of each volunteer. A more recent book, with new information on these lives, is Dennis Gordon’s, The Lafayette Flying Corps: The American Volunteers in the French Air Service.

Notable African Americans of Long Island

by Robert L. Harrison

Long Island’s African American community has a long and fruitful history. One of the New World’s first black African American poets was from Long Island, as was the first African American traveling baseball team. The world’s first African American combat pilot is buried here. Slavery existed on Long Island until New York State abolished the “peculiar institution” in 1820s, with African Americans leading a celebratory Fourth of July parade in New York City in 1828. Long Island was part of the Underground Railroad, and many African Americans volunteered to fight in the Civil War. African-Americans with Long Island connections of one sort or another have dined with presidents, performed for kings and queens, won Guggenheim Fellowships, composed award-winning music, entertained millions of people, composed poetry and received induction into several halls of fame. Poets, soldiers, playwrights, athletes, whalers, ministers, musicians, songwriters, laborers, civil-rights leaders – all took part in Long Island community from the beginning of European settlement. The following short biographies and histories outline the past lives of selected African Americans who were born, lived or were buried on Long Island (meant for the purposes of this article to include the counties of Kings, Queens, Nassau and Suffolk.

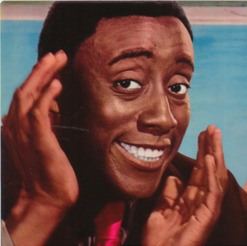

Louis Armstrong (1901-1971) “Satchmo”

Louis Armstrong was born in New Orleans into extreme poverty. His father left home when his son was still very young, and Armstrong’s education was limited at best as he roamed the streets looking for work. For a time he was taken in by the Karnofskys, a Jewish family of immigrant junk dealers who made such an impression on Armstrong that in later years he wore a Star of David pendent in their honor. At twelve, Armstrong was arrested after firing a borrowed 38-caliber handgun into the air to celebrate the New Year, resulting in his detention in the New Orleans Colored Waifs Home for Boys. Years later he declared it was the best thing that could have happened to him at this time, for the Home had a school band where he learned to play the cornet. Armstrong form this point dedicated his life to playing the cornet and, later on, the trumpet. He played wherever there was opportunity, from Mississippi riverboats to saloons, from New Orleans funerals to impromptu gigs on street corners.